You hear it all the time, especially from older collision repair technicians who’ve been in the business for 30 or 40 years: “The technicians today are ‘parts replacers,’ not body men.” The insinuation is that these modern-day techs are less skilled than their aged counterparts, don’t care as much about quality, and don’t have passion for their trade. These older techs lament the loss of the days when you could take the time necessary to do a high-quality job rather than rush out a “just okay” job to satiate the “fast and cheap” mantra of today.

But if techs today truly have lost the art of doing exceptional collision repairs, it might be driven not by disinterested individuals just looking to get a paycheck but by the demands of a changing industry.

Need for Speed

Mike West, I-CAR instructor and owner of Southtowne Auto Rebuild in Tukwila, Wash., who has been in the industry over 40 years, believes the “replace don’t repair” mentality of insurance companies over the last 10 years might have conditioned repairers for the worse.

“I think after 10 years of demanding high cycle time that you start losing some of those older techs who really can straighten stuff,” West said. “And for those [techs] who came up through that 10-year period, their ability to repair things has never been there, which is a problem now because things have now switched from ‘replace don’t repair’ to ‘repair don’t replace.’”

John Blaha, owner of Blaha Body Shop in Kewaunee, Wis., has seen this “replace don’t repair” mentality firsthand. He said he has seen estimates from other shops that customers bring in that indicate “new fender” when, based on his judgment, the fender could easily be repaired in two hours. Like West, he believes that the demand for speedy repairs for the sake of improving cycle time has been detrimental to quality and forced techs to under-utilize their skills.

“We’re making bad techs out of good techs because the shops behind them are saying, ‘Hurry up, hurry up, you have to get this done,’” said Blaha. “I think techs are cutting corners not because they want to but because they’re forced to.”

Brian Gilstad, assistant manager of Fisher Motors Collision Center in Minot, North Dakota, agrees with Blaha. He believes it’s now a “numbers game” all designed to cut costs, and techs are opting to play the game versus work for free.

“If you have an estimate that says you’re going to change that quarter panel in 16 hours, one way or another, guys are going to change it in 16 hours or less,” Gilstad said. “And what that’s doing is diminishing the end result. The product isn’t coming out like it should be because guys are cutting corners out there. It’s a numbers game.”

West agreed that this numbers game has significantly changed the industry.

“The average guy gets hammered daily by his shop manager who’s getting hammered by his insurance contacts because he’s got to meet the numbers. That has really changed our industry a lot,” West said. “Every once in awhile, however, you meet an inspiring guy who loves what he’s doing and you know he’s going to be successful because of that. But the reason he’s like that is because he has been insulated. He has a boss who’s supportive and has tried to send him to training.”

Blaha used the analogy of cooking a steak to show how speed can negatively affect quality.

“If a well-done steak takes 10 minutes, you can’t expect it to be done in three,” he said. “You could turn up the heat and get it done, but then it’s burned on the outside.”

Working for Free

Gilstad believes there are plenty of talented techs out there, but most have either left the collision repair industry completely or changed positions due to unsuitable compensation.

“There are guys out there who are completely capable of doing things, but the guys with real talent have left the industry,” he says. “They’re not on the floor punching the clock because they’ve just moved on, in some cases to the insurance industry, which eagerly gobbles them up.”

Gilstad says the lack of good techs out there is the main reason why he talked his dad into selling his shop instead of having him take it over.

“I told him, ‘What am I going to do when we need our next shift of guys?’ The craftsmen are totally going away,” he said.

Blaha believes the predominant compensation system used out there – flat-rate – is the culprit behind poor craftsmanship.

“I’ve never been a big believer in flat-rate,” says Blaha, who pays his tech hourly with a bonus at the end of the year. “So many smaller shops are flat-rate with guys turning out work that shouldn’t be going out the door.”

Young vs. Old

West doesn’t buy into the argument that the current generation doesn’t care as much as the older generation does. He acknowledges that there are differences between younger and older techs, but each bring something positive to the table. While older techs may have more skills, he says, the younger techs might just have more knowledge.

“While the guys coming out of vo-tech school may not have a lot of the manual skills necessary to do some of the more finite repairs on straightening or welding stuff, they may be better informed if they have an instructor who has taught them about advanced metals,” West said. “You always have that certain bunch of guys who think, ‘What do I need to be here for? I’ve been a tech for 30 years’. I get asked that all the time. Then, when you have the class, they find out, ‘Geez, I don’t know everything after all.’”

Kyle Steinburg, owner of Wenatchee Body & Fender in Wenatchee, Wash., also believes that both older and younger techs bring something to the table.

“I believe both the younger and older generations can learn from each other,” Steinburg says. “I see the younger generations having a better understanding of computers and the technology that’s put in today’s vehicles.”

But Blaha believes younger techs sometimes lack the patience and out-of-the-box thinking to address how a repair needs to be done.

“A lot of these young guys who are coming up through the ranks don’t take the time to think things through,” he said. “They have no clue where to start. For instance, sometimes a dent in a fender isn’t just about hammering it out. You may have to pull it before you even try pushing the dent out. Those kinds of skills have become a lost art.”

At the same time, West admits the attitudes of individual repairers young or old do come into play. He sees many repairers come through his I-CAR classes, and only a few exhibit the right attitude to become master craftsmen.

“You ask them, ‘Do you like what you do?’ And they say, ‘God, I love it,’” West said. “That’s only 10 to 20 percent of the guys out there. They’re guys like me who would do collision repair even if they could only subsist on it and not necessarily make a profit.”

Society of Collision Repair Specialists (SCRS) Executive Director Aaron Schulenberg believes that the more experienced techs have the unique ability to inspire younger techs to ensure that a care for quality lives on.

“Craftsmen-turned-owners, or ‘lead’ technicians, still have the ability to shape the younger generation entering the industry through mentorship, imparting the pride that resonates within our industry with an approach to the repair process that focuses on quality, integrity and pride,” Schulenberg said.

A Changing Industry

Jeff Peevy, I-CAR’s director of training, says that judging from the industry’s increased interest in training and staying up-to-date with the latest repair procedures, techs’ passion for collision repair today is as alive as ever. But like West, he believes a changing industry has altered the definition of a craftsman today.

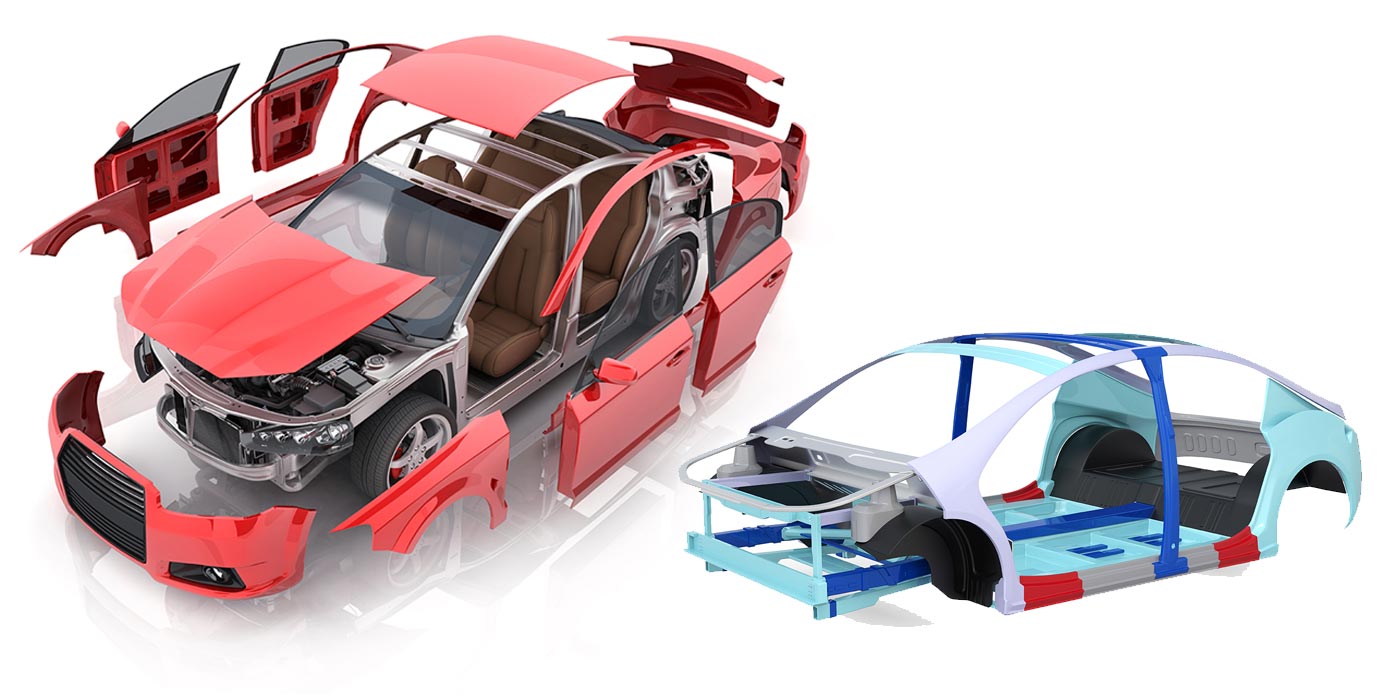

“I wouldn’t say there aren’t any craftsmen left – that’s a strong statement. I think our industry’s craft has changed, and the requirements for craftsmen have changed as well,” Peevy said. “Many years ago, I heard the same comment about gunsmiths. There was a time when they built most of their parts as opposed to ordering and replacing them. As metal technology advanced, parts became more than just shaped parts that fit. The same is true for today’s vehicles. So much has to be considered to not compromise the parts function as it was designed with other parts to provide a safer vehicle.”

Peevy is optimistic about the future of the collision repair industry based on the positive attributes of the younger generation of techs moving in.

“I see in the future a young generation that puts as much emphasis on knowledge as skill,” he says. “Skill is important, but to not back it up with current knowledge today is dangerous.”

Steinburg of Wenatchee Body & Fender agrees with Peevy that the industry has changed, and as a result, the definition of “craftsman” has changed.

“If your definition of a craftsman is an individual who knows how to work with lead and use a pick and metal file in order to straighten a fender, then the answer to the question, ‘Are there any craftsmen left?’ is no,” Steinburg says. “If your definition of a craftsman is someone who’ll measure a unibody car with a sonar measuring system, accurately pull a damaged vehicle back into square, section a frame rail and replace airbag systems, then I would say the craftsman is very much alive.”

SCRS’s Schulenberg said the same thing as Steinburg: what defines the craft in collision repair today differs from what it was in the past.

“Today, collision repair has become more of a process and less of an art,” says Schulenberg. “Technicians are trained on having the knowledge needed to repair today’s much more complex vehicles, and in many cases have more in common with scientific engineers than artists. The craftsmanship is still necessary to complete these highly technological structural repairs or to replicate the contours of modern vehicles, but advanced materials being used, such as high strength steels, aren’t repairable like mild steel was years ago. There’s also much more awareness of restoring a vehicle to pre-loss condition and the liability repairers have if they don’t do that.”

Room for Everyone

If there are more parts changers out there today, some people don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing.

“In my eyes, there is a place for those people, too,” said Mike Steinke, general manager of ABRA Auto Body & Glass in Eagen, Minn. “You don’t have to be a filler wizard to work in a shop.”

Steinke says out of the six technicians he has, one long-time veteran actually prefers to just bolt on panels.

“If something comes in that’s absolutely hammered, we’re going to let him replace it all day long,” Steinke says. “But am I going to give him a 10- to 15-hour dent? No, because that’s not his specialty.”

George Avery, claims consultant with State Farm, echoed Steinke’s feeling that the industry is big enough for people of all skill types and that “parts changer” isn’t necessarily a nasty label.

“Some shops have express lanes now, and so there may be a skill set that arises from this where that’s just what these guys are: parts replacers,” Avery said. “But that’s something the repair industry will have to decide.”

Avery feels that the industry has always had technicians who are better at fixing certain things than other techs. As a painter’s helper over 30 years ago, he says there were guys who would say, “Yep, I can fix that,” and other guys who would say, “Nope, that’s out of my ability to do that.” So for that reason and the fact that cars are more sophisticated now, he feels that to say the entire industry today is full of parts changers is just plain wrong.

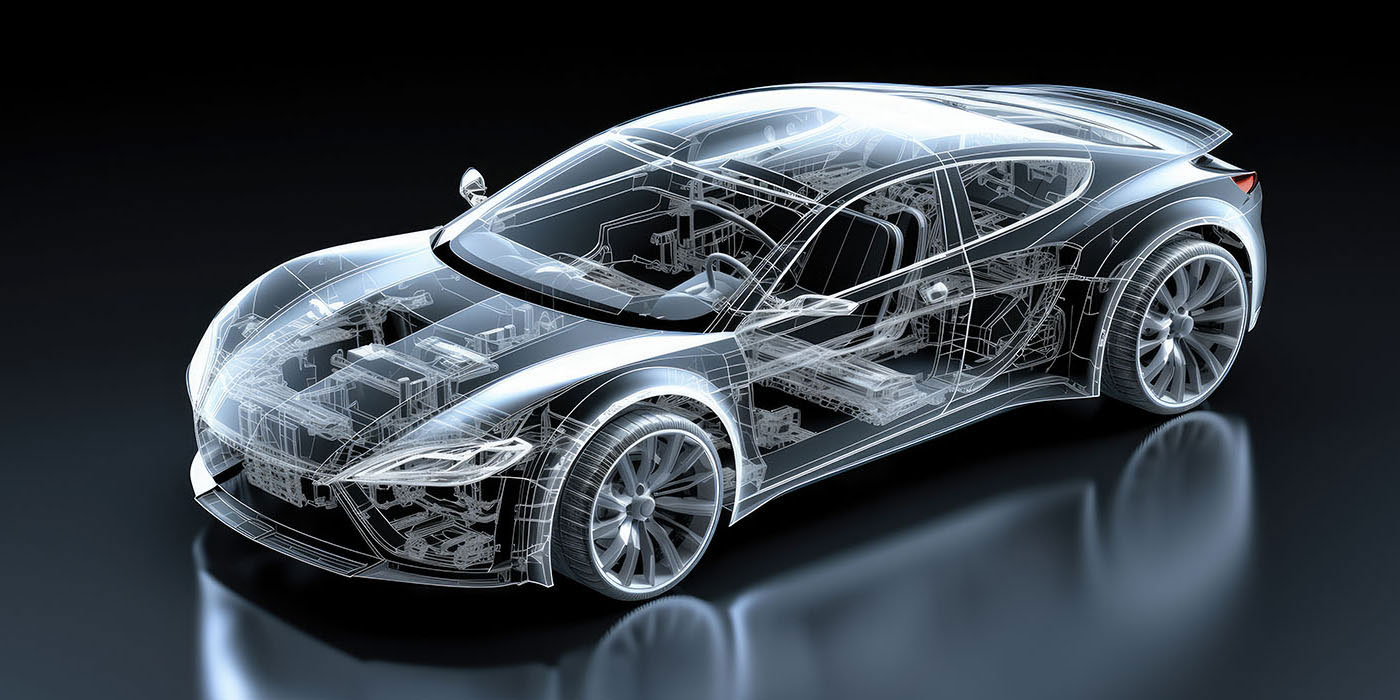

“When you’re attaching a frame rail and using an OE-required method, which could be adhesives and rivets, and then consider the size and location of the holes the rivets go in, how the rivets should be applied and the application of adhesives, that’s a little beyond just a parts replacer,” he says. “If you stack on top of that the job of refinish, I think you see that the repair industry still needs men and women who are true craftsmen.”

Like Avery, Schulenberg believes that repairers of all skill sets are needed in the modern-day collision repair facility.

“Highly skilled individuals are needed for the complex repairs, and lesser skilled technicians are being utilized on smaller, less complex repairs or in teams,” said Schulenberg. “This is a result of the economic pressures shops are faced with today and the landscape of the industry.”

“I Can Fix That”

Mike West considers himself a master craftsman, and the reason is simple: attitude. Whether you’re 21 years old or 61 years old, he believes this single attribute speaks more to a repairer’s potential than anything else.

“When I was on the ASE Board and watched as we gave out awards to the best in the industry every year, all of the winners would get on stage and say, ‘Well, I’ve just always enjoyed repairing the things that other guys couldn’t fix,’” says West. “So ‘willingness to learn’ was the overall theme.

“It’s also about being willing to accept the element of danger in a job you know you shouldn’t take on because the customer is a jerk, but then you think, ‘Could I satisfy this guy?’ And then you pick out the hardest thing in the whole job, look at it and say, ‘I can fix that,’ whether ‘that’ is the customer, the car or whatever.’”