Back in the early days of auto refinishing,

a spraybooth was any room with an open window. And a refinish

technician was anyone who owned a paint brush and had a vehicle

that needed painting.

It sounds alarming, but until the 1920s, painting

cars and furniture was done with a brush, and the problem was

as simple as removing the paint fumes from the spray room, i.e.,

a window.

But evolution was imminent.

The next step was to move the paint area next

to the loading dock door, which allowed more air exchange. It

wasn’t until Dr. DeVilbiss invented the atomizer (which later

became the first suction-feed spray gun) that overspray became

a problem. This made painting more complex and created the need

for spraybooths.

The earliest “real” booths I could

locate were updraft booths, from the 1920s, and the air-exhaust

technology from this era was used mainly for food preparation.

The exhaust hoods that pulled the greasy fumes away from frying

meat were then taken – enlarged – and mounted above the paint

area to remove paint fumes.

This was certainly a more positive ventilation

method than simply opening a window – but it proved to be inadequate

once spray guns were invented. When painters began atomizing paint

resin, the overspray particulate was too heavy to be sucked up

into the exhaust hood.

The earliest solutions to remove overspray

were as simple as installing a fan in the open window. The blades

of the fan pulled the paint cloud out of the room, rather than

waiting for a breeze to carry the cloud out.

This, however, led directly to another problem:

The blades of the fan were quickly covered in sticky overspray,

which threw the fan out of balance and burned up the motor. But

it wasn’t long before some enterprising painter made a discovery:

By mounting vertical wooden slats in front of the fan, some of

the overspray would collect on the boards before it could stick

to the fan blade. And so, arrestors were born …

These early arrestors worked better when mounted

in two rows and offset to each other. This way, the exhausted

air had to turn corners to reach the fan; each time the air turned

around the wooden slat, more paint would adhere. (These zigzag

slats were still only about 50 percent efficient. Plenty of overspray

still went onto the fan blades and into the exhaust duct, where

it became a major fire hazard.) Painters also began greasing the

slats to make the removal of paint buildup easier.

The 1930s: Is There a Fireman in the House?

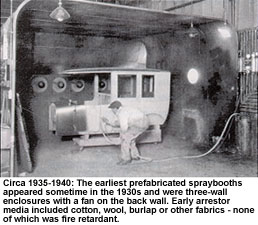

The earliest prefabricated spraybooths appeared

sometime in the 1930s and were three-wall enclosures with a fan

on the back wall. They often had a “box” of some kind

directly in front of the fan, with filter material mounted on

the front side of the box. Early arrestor media included cotton

wool, burlap or other fabrics – none of which was fire retardant.

The woven fabric did a much better job than

the wooden slats capturing overspray. But, since tightly woven

cloth plugged up quickly, painters had to change exhaust filters

several times a day. (Keeping an extra set of arrestors and intake

filters on hand is still good advice today.)

While this fabric did a better job catching

overspray, it also did a better job catching on fire: Solvent-

and paint-laden woven-cloth exhaust-filter media was extremely

flammable, and the frequent fires in early painting operations

are what gradually led to safer spraybooths.

The 1940s: Better Safe Than Sorry

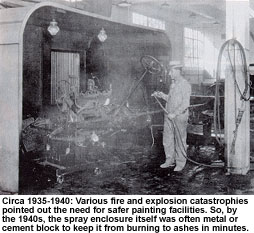

Various fire and explosion catastrophies pointed

out the need for safer painting facilities. So, by the 1940s,

the spray enclosure itself was often metal or cement block to

keep it from burning to ashes in minutes. These slightly safer

booths also had light fixtures in houses rather than directly

in the path of paint overspray.

About this time, auto spraybooths became totally

enclosed with drive-in doors on the forward side of the open booth.

Keeping the doors closed contained the overspray much more effectively

and kept it off everything else located within 20 paces around

the car.

The 1940s also brought us better methods to

capture overspray. Treated paper leafed together or spun fiberglass

both did a better job trapping paint particles on their way out

of the booth. They were also less flammable. (But don’t fool yourself.

Those fancy flame-retardant fiberglass arrestors in your booth’s

floor right now will burn really well if exposed to a spark!)

The 1950s: Hitler Inspires Downdrafts

Many people I spoke with for this article

attributed the technology widely used in today’s downdraft spraybooths

to Adolph Hitler. The story goes something like this: Hitler was

trying to hide both manufacturing capacity and troops underground

and away from prying Allied eyes. To evacuate fumes from welding

and smelting operations or to simply exchange air so troops could

breathe, German engineers invented downdraft technology. This

technology pushed fresh air in on the top, pulled spent air from

a trench below floor level and then ducted it back to the surface.

After the war, most of Europe’s industrial

base was in shambles, and few old-style spraybooths had survived

the bombing. So, when it came time to rebuild and reconstruct

new spraybooths to paint cars – either at the OEM level or the

refinish level – downdraft air flow was the logical choice.

Because painter health and safety became an

issue in the 1950s, especially in Europe, downdraft technology

was also a healthier choice. Downdraft air flow keeps harmful

paint fumes and vapors away from the painter because it quickly

sucks them down into the floor trench.

In the United States, the 1950s’ safety issue

was more about fire prevention than painter health. The invention

of electrostatic painting required a big improvement in spark

and fume control. Painters still pulled overspray across the car

from one end of the enclosed box to the other, but sprinklers,

grounding technology and spark containment made the environment

less likely to explode or burn.

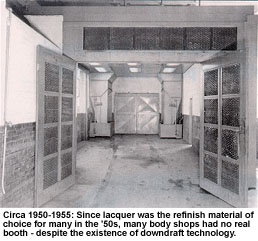

Since lacquer was the refinish material of

choice for many in the ’50s, many body shops had no real booth;

a “paint room” with a fan on one wall sufficed for many

painters across the country. Because lacquer dried so quickly,

the overspray didn’t go nearly as far as the sticky synthetic

enamel overspray. (And, many painters concluded that painting

cars had to take place in an overspray cloud – and that it was

simply time to pause between coats when they couldn’t see the

car anymore!) Also, since painters had to polish lacquer to a

shine, the dirt that did collect in the finish wasn’t critical

to most shops.

The 1960s: Protecting Painter Health

By the 1960s, many municipalities around the

country had adopted rules and regulations about spray painting.

As new body shops opened, they were forced to install an appropriate

fire-proof spraybooth.

In Europe during the 1960s and ’70s, painter

safety was still a driving issue, so downdraft booths continued

to be the norm. (The hazardous particulate is as much as 15 times

lower in a downdraft booth than in a crossdraft booth.)

Since many European countries have socialized

medicine, it was easy for the government to track how many visits

to the doctor a particular painter made. With only one health-care

provider, it was also clear how hazardous auto paint could be

to an unprotected painter.

In addition, our entire industry was regarded

much more professionally in Europe than it was here – possibly

because the purchase of an automobile represented a much larger

portion of a person’s net worth in Europe than it did here. (In

Europe, collision repairers were expected to restore the car to

true preaccident condition because the owner would still be driving

it many years later.) Europeans saved their entire lives for a

car, while American vehicle manufacturers suggested you buy a

new car every year – “You don’t want to drive last year’s

chrome-finned wonder, do you?”

The 1970s: “Real” Booths Gain

Acceptance

The 1970s saw improvements in filter efficiency;

both intake and exhaust filters became better. More American body

shops were interested in a real paint booth, not just to comply

with local codes, but to keep paint work cleaner.

Even when the door rate was $10/labor hour,

it still cost money to polish all the dirt out of the car before

delivery to the customer. Confining the spraying to a fireproof

room with 10,000 cubic feet of air per minute rushing through

it made for safer, cleaner, faster paint work.

At the OEM level, the 1970s saw the first

practical application of robot painters. By keeping the human

painter out of the spraybooth, health issues ceased to be a problem.

Unfortunately, there are too many variables in refinish painting

to make a robot practical for body shops.

The 1980s: Downdrafts Get Their Big Break

The 1980s really were the birth of the modern

body shop. Until the arrival of the unicoupe car in the 1980s,

the most expensive piece of equipment in most American body shops

was the $10,000 crossdraft spraybooth. When car construction changed

with General Motors’ “X Body” Citations, body shops

discovered the need for equipment to measure, pull and hold these

frameless cars. And it took a healthy $25,000 to acquire a suitable

rack/bench for this. Progressive body shops, however, soon discovered

it was possible to recover their huge investment – and to create

a dandy profit center with their new frame rack.

Not only did the arrival of the unicoupe car

change everything, but top body shops also began seeing the advantage

of downdraft air flow. Creating a curtain of air around the car

kept the paint cleaner and dried it faster.

I think it’s safe to say the driving force

behind downdraft booths in America was productivity – not painter

safety, like in Europe. As vehicle manufacturers began the switch

to base/clear finishes, top shops looked for better ways to refinish

cars. They had already established they could make a $25,000 frame

machine pay its own way; surely they could recover the cost of

a better spraybooth in increased production. These shops were

quick to realize that a 75 percent reduction in buffing time was

a barrel full of labor dollars at the end of the day.

Clearcoats vaulted dirt to the head of the

painter’s problem list. For one thing, more coats were needed

– and every trip around the car stirred up more dirt. Also, there

was no pigment to hide an imperfection; instead, the clear magnified

the dirt. To deal with these problems, painters realized the advantage

of moving a lot of air in a tight curtain around the car: The

paint dries much faster.

By the mid-’80s, three or four European booth

vendors were selling auto-refinish booths. Some early body shop

customers can tell a terrifying tale of trying to read instructions

in a foreign language or trying to hook up 50-cycle motors to

60-cycle currents.

The late ’80s saw the widespread introduction

of prep stations to American body shops. Confining sanding dust

goes a long way to keeping the paint work clean. And downdraft

air flow worked very well for capturing sanding dust.

It was also possible to paint under the curtain

of downward moving air. But, since there were no walls around

the prep station, problems arose when local inspectors objected

to open power outlets around the spray area. Without walls to

define the “spray area,” the spray area soon became

a 20- or 30-foot radius around the prep station.

Most shops had open 110-volt outlets and other

hazardous operations within that circle. It wasn’t a problem when

the unit was used only to collect dirt. But when the shop started

to prime or paint under the prep station, some municipal inspectors

objected. (Prep stations continue to be popular paint shop equipment.

Just make sure you and the local inspectors are on the same page

before you install one.)

The 1990s: A Decade of Advancements

As we all know, the 1990s brought many desirable

changes to spraybooth technology. The early part of the decade

saw an increase in the firms offering “shop design”

services. New-car dealers, in particular, climbed on the consultant’s

bandwagon and remodeled their 1970-vintage body shops. (No matter

what your business, there’s a good case to be made for getting

professional help from someone familiar with your specific problems.)

Shop design these days almost always includes

a downdraft spraybooth, for both health and productivity reasons.

Newer booths incorporate the latest filter technology. And trapping

the dirt on the way into the booth and trapping the solvent and

particulate emissions on the way out have improved markedly in

the last few years.

The newer booths also offer either a direct-

or indirect-fired air-replacement furnace. The race is on to see

who can heat the most air for the least cost and force dry the

most cars.

As you may already know, so much of what makes

a spraybooth work is best explained through physics. But who knew

physics would turn out to be important? I had my head down on

my desk for most of my physics classes! Air movement, air velocity,

back pressure, water-column pressure, temperature rise and more

play important roles in quickly painting a vehicle. Also, a delicate

balance exists between the shape of the intake plenum, the depth

and shape of the exhaust trench, and the size and style of the

fans. Little changes in design do make a difference. Make sure

your booth vendor explains the company’s design philosophy and,

if possible, visit a similar booth installed at another shop.

Every booth design looks good on paper; not all work equally well

in the real world.

The Next Millennium: Smart Booths

What will the future hold for spraybooths?

Hey, if I knew that answer, I’d have been on top of the stock-market

rise, and I’d be writing this article from a beach in the Caribbean!

But I’ll do my best to give you some predictions, anyway.

For one thing, booth manufacturers are now

matching temperature, air flow and cure times in their booths

to a specific paint product from a particular paint line. It’s

getting to be an exact science when the directions call for 74

degrees F, 100 feet per minute of air past the car and a 12-minute

cure at 175 degree F for one particular clearcoat. Changing the

spray-gun fluid tips and air caps, painting temperature, air flow,

purge, cure times and temperatures for one specific product seems

like a lot of hassle. But if the changes produce more work at

the end of the week, they’re well worth the adjustments.

Other likely advancements include a phone

modem attached to the booth. This modem will call the booth manufacturer

at regular intervals and download all the information from the

last 15 or 20 paint jobs into their computer. The booth manufacturer’s

computer will then compare the shop’s actual spray time, spray

temperature, purge time, cure time and temperature to the ideal.

Potential problems could be corrected before they ruin paint work.

For example, if the booth of the future detects an increase in

back pressure as the exhaust arrestors plug up, it will sound

an alarm to alert the painter.

Eighty Years of Advancements

It’s been a long road to get where we are

today. We’ve gone from the days of painting next to an open window

to the days of a $75,000 spraybooth that’s smarter than we are.

What does this tell you? It tells you that

if you’re still painting cars in a crossdraft booth (or spray

room), a new downdraft should be on your want list. Not only will

your painters work in a healthier environment, they’ll produce

more – and better looking – paint work.

Cars have changed, paint has changed and consumer

expectations have changed. If your shop hasn’t changed, maybe

now is the time.

Mark Clark, owner of Clark Supply Corporation

in Waterloo, Iowa, is a contributing editor to BodyShop Business.