It seems that everything we do today in the collision repair industry is viewed in a legal context. Direct-repair programs, an enduring subject of controversy, are no different.

The DRP controversy rages on today, although the proliferation of preferred shop programs over the last 10 years has made the debate almost rhetorical. Today, it’s often not a question of whether to DRP, but which DRP. Still, there’s strong resistance to the programs in some quarters of the industry.

There are those who claim that DRP shops cannot possibly deliver proper repair work with all the concessions, labor discounts and aftermarket-sheet-metal-usage requirements. In response, DRP advocates say their detractors know nothing of efficiency, the economies of scale and advanced business management. Both sides have their valid points and, as usual, the truth lies somewhere near the middle.

However, there is consensus that the quality of repair work in general has slipped from the previous standard of pre-loss condition to that of commercially acceptable. It gets by – sometimes barely, which I might add, isn’t something for which you’ll find insurers making excuses.

Street-level claims personnel will tell you that something is commercially acceptable, or that a mangled, but straight, frame rail is only cosmetically damaged. This is NSU (“not so upsetting” or “non-specific urethritis,” depending on whom you’re talking to). Because repair work can’t be perfect-back-to-new, virtually everything is a compromise at best, which means someone is often called upon to be the arbiter of how good a compromise it has to be. Claims people like to say, “That’s fine. That’s OK in terms of what you get in the industry.” It’s always a matter of what’s reasonable, a term that’s inherently subjective.

Due to this, and other, points of contention, the DRP debate has moved from industry forums like the Collision Industry Conference, past the hotel bar and on to the courthouses (while the concept itself has been – and still is – on trial in a number of respects).

Are DRPs legal? In a word, yes. In the absence of a state statute barring a system of referrals for claimants and insured, such practices are a well-entrenched staple of the property and casualty business. From the repair of smoke and fire damage to glass replacement on buildings, homes and autos, entire industries both thrive and depend on insurance referrals.

But is a referral from a payer inherently conflicted in terms of the interests of the payer and payee? And what of various state regulations that are apparently trampled in the furtherance of an insurer’s attempts to direct work? Clearly conflicts exist, yet the odds of dismantling entire systems based on the intricacies of various state regulations are slim.

Rhode Island Victory for DRPs

One of the most significant court cases is that in which Crown Collision Center, Inc. fought the State of Rhode Island’s Department of Business Regulation, which was attempting to shut Crown down. The state was claiming that in its operation of a DRP, Crown was acting on behalf of USAA as an unlicensed insurance adjuster.

Crown won the case – Crown Collision Center, Inc. v. Thomas Schumpert and Marilyn Shannon McConaghey, in their capacities as former and current directors of the Rhode Island Department of Business Regulation – and the ruling was upheld on appeal early this year by the Rhode Island Superior Court – leaving the Crown Collision Decision (as it’s become known in that state) as the rule of law with respect to DRPs.

In essence, the Crown case was about the incongruity between state regulations that stipulate who can and can’t write an appraisal pursuant to an insurance claim for the repair of collision damage. Says Christopher Sheehy, an independent appraiser in Rhode Island: “Despite the court’s ruling, when you read the bylaws, [the DRP arrangement] still goes against the laws concerning who can write an appraisal.”

While this case only made law in Rhode Island, its significance around the United States is substantial because the case could be entered into evidence in a court in any state. The fact that the Rhode Island Superior Court scrutinized the decision gives the case more weight than you might expect for a ruling coming from tiny Rhode Island.

“The court’s decision brings to a close many years of confusion over the direct-repair concept, and reaffirms the value of this system for Rhode Island consumers,” says National Association of Independent Insurers Senior Counsel Gerald Zimmerman.

In its summary, the court concluded that the “Motor Vehicle Damage Appraisers act was enacted to prevent the potential conflict of interest between appraisers and automobile body repairers.” It went on to state that the “statutory prohibitions reflect a public policy established by the legislature to prevent abuses that could arise if appraisal and repair activities are not segregated.”

Crown argued that “rather than seeking to affect the direct-repair relationship, the General Assembly was more interested in preventing collusion between appraisers and repair shops that would operate to the detriment of the consumer.” Apparently, the legislators were more concerned with an alliance that would serve only to jack up prices, which as we know, is not the basis for DRP relationships.

The Rhode Island Superior Court held that the intent of the legislation that prohibited shops from settling claims was to prevent fraud and unbridled charges. In other words, the effect of the insurance adjuster was that of control over runaway repair costs. The court was satisfied that USAA Insurance, in this case, was maintaining a sufficient capacity as an auditor and that as such, a DRP relationship wasn’t inconsistent with the intent of the lawmakers. It concluded that the relationship between USAA and Crown was a consumer friendly one and didn’t violate the intent of the law.

Crown was a major victory for the insurance industry and will provide a hurdle for potential litigants attempting to dismantle the system of DRPs. It would seem that the overriding concern of state lawmakers was to prevent gouging by body shops and high prices, as opposed to possible circumvention of an open and competitive market. That issue has yet to be addressed.

The Next Step: Tortious Interference Lawsuits

Does the Crown case mean the fight is over? Hardly. Legal challenges are being mounted constantly, some of which seek class-action status. More significantly, a handful of shops harmed by the loss of business attributable to their customers being lured to DRPs are gearing up to sue for tortious interference. That route, however, can be a very rocky road. You must prove that your customers were, in fact, lost to the DRP programs and went there under duress. But the hardest part is to quantify how your business was harmed by an alliance between your customers’ insurance companies and your competitors.

“Proving damages is hard,” says Lee Allman, a Philadelphia lawyer with experience in bringing these cases. “They’re going to open your books and look at tax returns. If you can’t show a loss in business or even substantiate a loss in the rate of sales growth, you’ll be hard pressed to find an attorney to take the case.”

Adding to that difficulty, claims departments are far more cautious these days in their word tracks designed to get customers to take their vehicles to DRP shops. As a result, claims personnel are loathe to actually speak badly (on the record, of course) of an independent shop, so their inducements are somewhat left handed. For example, one might say that if the insured went to the preferred shop, there’d be no hassles, no excess charges and no delays. The implication of such statements is that the insured would experience all those penalties if he went where he originally intended to take his car. Such allusions to hardships may not cross the tortious line, but they certainly hang way over it.

Are Consumers Being Hurt?

A perspective that no one may have considered in the DRP controversy and the arguments against it was recently articulated by Louisiana shop owner Ann Spink. Spink asked: “If I hire someone to repair something for me – let’s say my car – and they’re willing to give a discount – let’s say 10 percent off the price of the parts – shouldn’t I be the one to benefit from the discount?

“If they give those discount dollars to someone who wasn’t a party to the repair contract, wasn’t that money stolen from me? Can you imagine buying a sofa on a 10 percent off sale and the furniture store giving the 10 percent to the radio station that ran the commercials? Can someone please explain to me why DRP shops are allowed to steal from their customers by giving these moneys to the insurance companies?”

Clearly, the most viable of legal strategies challenging DRPs are those dealing with consumers and how they’re affected. One approach examines what an Actual Cash Value policy promised the insured.

“Insurers began to provide PPO-type benefits without changing the insurance contract,” says Ron Parry, a Kentucky lawyer with extensive involvement in the collision repair and insurance industry matters. “The entire problem is that they’ve gone to an HMO situation without offering a discount to their policyholders for giving up choices regarding how their cars are repaired. It’s managed care. … The auto insurance industry has gone to an HMO.”

In terms of a DRP being legal, Parry says that he doesn’t think there’s anything that prohibits it. There’s no “barring state regulations for unsolicited referrals.”

Of the exclusive nature of the DRP programs and their thwarting of the free market when policyholders and claimants are cajoled into spending the proceeds of their claims settlements in company shops, Parry says: “It’s one thing to have a DRP system, but it’s another to beat up on shops.”

Perhaps the most vulnerable part of the DRP is how it’s operated. That is, what effects do the discounts and lack of oversight have on policyholders’ cars? Are the discounts (called kickbacks by some) inherently prohibitive in terms of a body shop’s ability to deliver proper work? Perhaps at the upper tier of repair shops that employ the best technicians and are equipped and situated as best as possible, discount repairs can also be quality repairs. But in reality, negligence is spread across the entire industry, and downward economic pressures cannot help but erode repair quality.

Case in point is a lawsuit filed in 1997 by a Pennsylvania policyholder who was directed by Nationwide Insurance Company to a dealer’s body shop – which proceeded to cost shift the bill, to repair parts that appeared on the invoice as having been replaced and to do a generally poor-quality repair job.

In Berg v. Lindgren Chrysler-Plymouth and Nationwide Insurance Company, the complaint alleges (among other things) that the discounts offered to Nationwide in order to obtain the referrals were excessive to the point where a qualified shop couldn’t provide a quality repair. The plaintiff also alleges the insurance company had knowledge of its Blue Ribbon shop’s incompetence, yet continued to refer insured motorists to the shop.

The suit’s still in the motion-filing stage, with each side jockeying for advantage in the court regarding what is and what isn’t admissible as evidence.

Their Lips Are Sealed

When I first contacted Progressive Insurance Company for comments on the DRP issue, they were very enthusiastic about having an opportunity to contribute their corporate perspective.

At first.

However, their spokesperson, Mary Beth McDade, withdrew her offer to participate without citing a reason. I asked her, as well as the media-relation offices of several major auto insurance companies, to comment on the existence of a potential conflict of interest in such a relationship. My questions for McDade were:

- What legal challenges (if any) does Progressive see ahead for the operation and expansion of their preferred body shop programs?

- Is there an inherent conflict of interest in a payer referring work to a service provider, more specifically, one that offers a discount to the insurer?

- Who’s the customer in these programs? Is it the insured or is it the insurer?

- How does Progressive cope with the restrictions placed on claims representatives by the various state insurance departments and regulations pertaining to referrals?

- Could you describe Progressive’s preferred shop program and how it offers better service to your insureds?

I’m still waiting for an answer. From anyone.

Watch the HMOs

DRP is the issue of the body shop business, there’s no denying that. And faced with these nagging questions and the eventuality of having to answer them in a court of law isn’t a matter easily dismissed by the insurance industry. Based on what’s at stake here, the insurance industry will devote what it takes for the defense of the DRP – presumably a massive amount of resources.

One to watch is a recent class action lawsuit filed by legendary antitrust lawyer David Boies against a number of HMOs, in which plaintiffs allege that operation of them is nothing short of a racket as defined by the federal RICO statutes. What will be on trial in the HMO case is a third-party payer’s ability to interfere in the delivery of professional services.

“These cases aren’t sensible law. They’re based on sand,” says Stephanie Kanwit, counsel for the American Association of Health Plans. “Nobody likes to be called Tony Soprano.”

Maybe not. But can these cases really be dismissed that easily?

“Those of us who believe in a free-market economy … in private enterprise and the social and political benefits of a democratic society, which are highly correlated with free-market economics … believe antitrust laws are a critical component of public policy,” says Boies, who’s also been involved in the attempts to revive the 1963 Consent Decree and is no stranger to the collision industry’s issues.

The health care debate explores the fundamentals to the DRP, which make this a potential bellwether case for our industry, too. And if the HMOs fall, the auto insurers are right behind them.

Writer Charlie Barone has been working in and around the body shop business for the last 27 years, having owned and managed several collision repair shops. He’s an ASE Master Certified technician, a licensed damage appraiser and has been writing technical, management and opinion pieces since 1993. Barone can be reached via e-mail at [email protected].

|

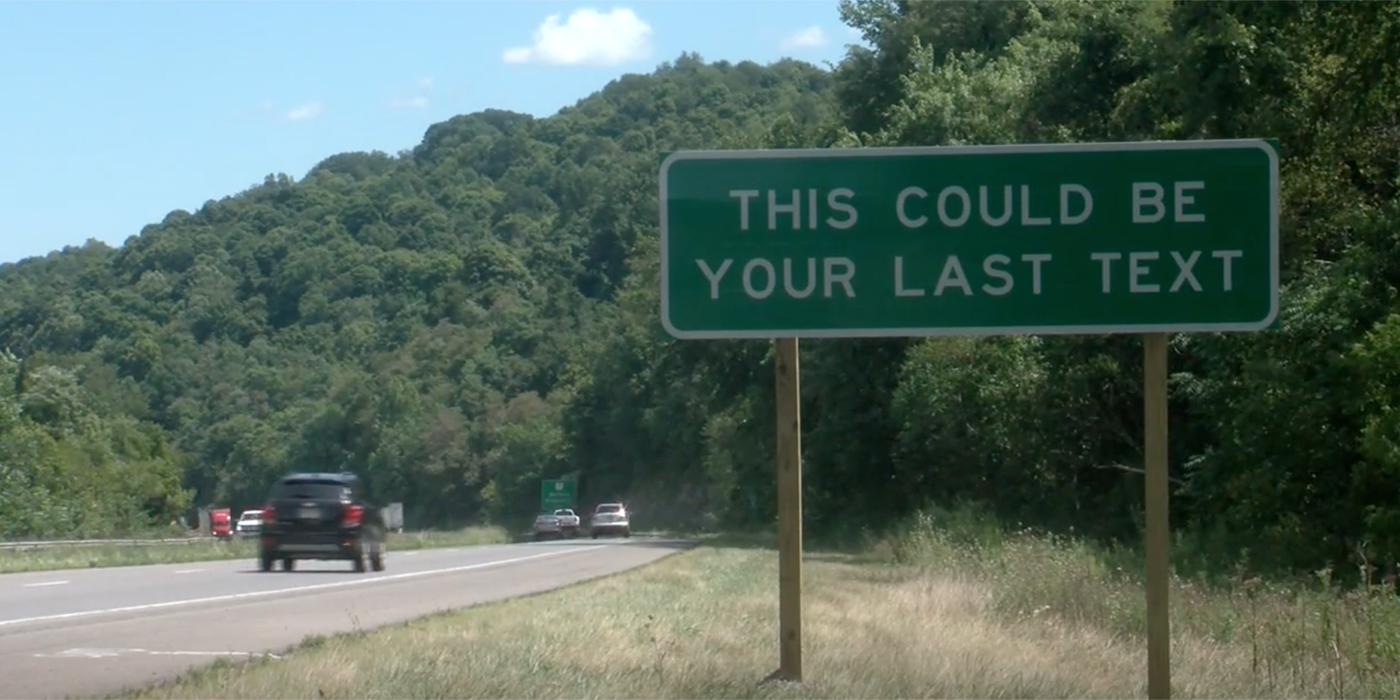

Payer Controlling Quality = Conflict of Interest Amway, but Better: “Referrals are nothing more than networking – usually a valuable tool … for any industry in a [capitalistic] society,” says Littleton. “However, there’s a conflicting interest when the financially responsible party (or payer) also controls the quality of repair work.” Conflict of Interest “Obviously, the insurance carrier wants to pay as little as possible. In fact, job performance for adjusters is measured by average dollars paid per claim – even though this is denied, hidden or often called something else. And, just as obvious is the property owner’s interest in high-quality restoration – we’re not talking betterment – to protect her investment. “With their respective interests, the payer (the insurance company) would require repairs based upon lowest cost, and the property owner would require repairs based on quality without regard to cost. Everyone would agree that the payer shouldn’t issue to the property owner a blank check for repairs. This isn’t a realistic concern. It’s equally true that the payer shouldn’t control the quality of repair work – a very real concern. In an ideal world, an independent repairer will provide quality repairs at a fair cost.” Pick Your Poison “It’s always been apparent to me that the repairer will have to decide who is her real customer. Is it 1.) the payer – the insurance carrier who sends the business in most cases and without whom the repairer has much less business? Or 2.) the property owner who wants the vehicle as though the accident never happened? It’s impossible to have both as your real customer because of the inherent conflicting interests. …” Fighting for Independence “I’ve met very few repairers who can monetarily afford to remain independent in their collision repair work. I admire those who’ve chosen to recognize the property owner as their customer with the hope that fair dealing will bring the same business most likely lost by refusing to sell their professional judgment to the insurance industry.” Advice to DRP Shops “For those shops that have successfully blurred the line between the repairer and the insurance carrier, I continue to urge them to take a hard look at the medical profession, where the insurance industry dictates care and costs. DRPS are the Ômanaged care’ of the collision repair industry.” The Legalities of DRPs “The question isn’t whether they’re legal. The question is whether they’re desirable. My answer is a resounding no. It makes no more sense to me than standing at the scene of an accident and allowing the at-fault driver to tell me where to take my truck across town for repairs, how it should be repaired (imitation, poor-fitting parts with no galvanization) and how much he’s willing to pay for repairs (the lowest bidder). Without the independence of the professional repairer, there’s no difference between the DRP and the insurance company – just a different organization with the same interest, adverse to the property owner.” You May Also LikeCollision Repairers: Will You Take the Oath?Today’s collision repairers are challenged with a new set of concerns, one being the need to follow OEM repair procedures. Last month in my article, “The Right Way, the Wrong Way and Another Way,” I brought up collision repairers’ professional responsibilities and the notion of the collision repair industry developing and adopting an oath of professional ethics and conduct much like that of the medical industry’s Hippocratic oath, “To Do No Harm.” Three Generations Keep Trains Running on Time at CARSTAR JacobusCARSTAR Jacobus Founder Jerry Jacobus and son Dave share a passion for collision repair and also model railroading.  Auto Body Repair: The Right Way, the Wrong Way and Another WayIn a perfect world, every repairer would make the right decisions in every repair, but we don’t live in a perfect world.  The Digital BlitzWe talk so much about how much collision repair is changing, but so is the world of media!  Auto Body Shops: Building a Foundation for the New YearFor the new year, it’s important to conduct a thorough audit of your finances to look for areas of opportunity and things to change.  Other PostsAuto Body Consolidation Update: There’s a New Buyer in TownThe good news for shops that want to sell but do not fit a consolidator’s  Is Your Auto Body Shop a Hobby … or a Business?So you want to provide safe and properly repair vehicles to your customers … even at a financial loss?  BodyShop Business 2023 Executives of the YearGreg Solesbee was named the Single-Shop Executive of the Year, and Charlie Drake was named the Multi-Shop Executive of the Year.  This Could Be Your Last TextA sign I saw on the highway that said “This Could Be Your Last Text” reminded me of my son’s recent car wreck.  |