In 1984, direct-repair program (DRP) – the original Allstate

PRO System – was virtually unheard of. Although the concept had been tested on the East Coast and in some of the big cities, most body shops had never been introduced to the idea.

One spring day, two people – known as “inspectors” – from Allstate came to our door. They asked if we were interested in being “checked out” to see if we were good enough to be on their new repair program list. We agreed.

Why? We were in a position where we wanted to be financially stable. Although we used I-CAR for training and had ASE-certified techs, and owned a couple frame racks, a spraybooth and MIG welders, we felt we needed more.

The inspectors returned the next week and did a much more thorough “check-out.” (To be honest, they did a lot more than I expected them to.) Allstate had been to every shop in the area and had listed comparisons of equipment and training. They knew where they wanted to start shopping for a DRP.

They asked us about financials – which we refused to show them. They also asked to see our state UDL License and sales tax certificate, and wanted us to install a computer system for estimating and sending the information to the insurance company. (At the time, the CCC information system was called Ez-est. We’d been wanting to computerize for some time, so this was our excuse to do so. It was an expensive request – a three-user system cost $20,000. And we couldn’t get by with the one unit, considering we already had way too much volume for one.) They also talked with our technicians about attitude and a new trust and bond that could be developed.

The inspectors explained that Allstate wanted a few concessions for this arrangement, but I didn’t feel like I was signing my name in blood. They wanted a cut in labor and domestic parts discounts, but for these, they promised to increase our volume by at least 20 percent. The inspectors also went through their contract with us and said it was a take-it-or-leave-it contract. I told them this was a big decision and I needed a little time to think it over. They gave me a week.

Before they left, however, they told me that we were the shop they really wanted. They also reminded me that they were signing only one independent shop and one dealer in our area.

All of my so-called “friends” in the business told me this was a big mistake. “Don’t give in to them,” my friends told me. “They’ll own you.”

But we were proud to be the “chosen” shop after such a rigorous review. On the downside, we were receiving hate mail and phone calls – I assume from other shops. They said that it would be the beginning of the end and that insurance companies would take over the industry. We were even asked not to come to any more local ASA meetings because we’d no longer be “one of them.”

The time finally came when I had to make a decision. When they returned in a week, we negotiated a better deal – one we could live with – and signed the contract. It was a contract that either of us could cancel with 30-days notice.

With much grief, I conceded to join the ranks of the DRP world. A 20 percent increase in business is hard to come by. We were a $1-million shop at the time we agreed, so a 20 percent increase looked really good. Today, we’re a $4-million shop. I can’t say for sure if Allstate contributed to our growth, but it does seem entirely possible, along with all the other DRPs we now have.

When we signed on with the Allstate DRP program in 1985, it opened many other DRP doors for our shop. For example, after Farmers insurance developed their program, they came to us, too. They’d heard we were an “Allstate PRO Shop.”

It’s amazing the amount of criticism we received from our competitors for joining a DRP program. However, it’s interesting to watch how quickly the DRP spots fill up when a spot is available – generally by the shops that criticized us the most.

What have I learned? There are a lot of good things about direct-repair relationships – and also some not-so-good things. There are even a few really unpleasant things that can happen when you work with DRPs.

The Good, the Bad & the Ugly

The very best thing about being part of a DRP is that it produces volume that makes money. If the stalls were empty, they’d cost you money. (Of course, you don’t want to take on a DRP to lose money – and shame on you if you are losing money.)

Another good reason to have a DRP relationship is the instant credibility it gives you with other insurance companies that are thinking about using your company. They know you’re a reputable company and know the basics of a DRP. Some companies just add us on to their system simply because we already have CCC-Pathways estimating systems.

On the downside, not all insurance companies use CCC for their connection to the shop; others use ADP. So we’ve doubled the cost by having to carry two estimating systems. (Why can’t they all be on the same system, I ask?) Some companies also want us to add a DSL line at an additional expense to us. So far, I’ve resisted.

One thing we’ve gained from joining DRPs is additional training for our staff. DRPs often require additional and up-to-date training and encourage us to keep our techs current. Due to their requirements, we have a high-tech staff who’s well-trained in various areas of the industry.

Another good thing about DRPs is that 99 percent of the time, you write your own bid. You don’t write a dishonest bid or a competitive bid; you write a fair bid covering all items. That’s where so many people go wrong with DRPs – they still write competitively. With a fair bid system in place, you write all your R&Is, all P-pages, all processes and all damage. If you don’t make money on the bid, it’s your own fault.

Dealing with all the different rules and regulations while keeping all the insurance companies happy is the most difficult problem we face. Many adjusters forget that you have other work besides theirs and get upset when you can’t come to a screeching halt just for them. We have a business to run that they’re a big part of, so we try to take care of them and keep our opinions to ourselves. They rarely care what we think anyway.

Case in point: One time I fixed a T-bird by pulling a badly damaged quarter panel instead of replacing it, saving at least $1,700 on the job. On the same repair, we replaced a fender and repaired a little damage on the core support. When the adjuster came to reinspect, he said I paid myself $0.02 too much on blending the core support. I said, “What about the $1,700 I saved you on the quarter?” He said that’s what I was supposed to do – save money – and did I expect him to overlook the $0.02 of an hour?

Another time, I had a $13,000 repair on a full-sized van. We billed the insurance company for repairs. After three weeks, I called to check on payment, and the adjuster said they weren’t paying because we didn’t send any photos. I admitted that we forgot photos, and he still said he wasn’t paying. I said that was fine, but where did he want me to tow the other four jobs of his that were in the shop and what did he want me to tell his customers? After a short pause, he said he’d pay this time but threatened not to do it again.

Another ugly event was on a $10,000 repair for a DRP. We sent pictures and we knew the appraiser had the file, but 30 days went by and we still hadn’t been paid. I called him and asked why he hadn’t paid the bill. He said that we knew they only pay $2 for hazardous waste removal, not $3. He was waiting until I called and asked him about it as my punishment. I told him he’d better send a check today and adjust his dollar. I also let him know that I didn’t appreciate being treated like a child. I told him I was considering quitting his DRP, and he told me that was good because there are plenty of fish in the sea. I’m no longer one of their fish. We parted ways in March.

If you can’t handle having all these bosses when you thought you were the boss, then DRPs aren’t for you. Every one of them thinks you should bow down when they walk through the door. We’ve built a business on trying to get along with everyone – although this can be unpleasant at times.

A Few Words of Wisdom

While the DRP doors opened quite easily for us, it obviously takes a lot of hard work to maintain a healthy relationship with insurance companies.

The first thing you have to realize is that each insurance company has its own way of doing business. Let’s say Allstate doesn’t care about photos. But at American Family, an inside appraiser said, and I quote: “No photos, no payment.”

Second, you must remember that insurance companies don’t care how their competitor does it. When you’re talking with a Farmers appraiser and he tells you that he wants a procedure done a certain way, you might have an itch to say, “Progressive does it this way, and we think it works well.” But the Farmers agent isn’t concerned with how Progressive does it. He wants it done his way or no way. It’s a love-it-or-leave-it attitude that seems to guide each appraiser’s relationship with the shop. They have a dozen other shops vying for the spot you’re in as the “chosen” DRP shop, so when Farmers comes in, it’s smart to put on the Farmers insurance hat. And when Allstate comes by, change hats.

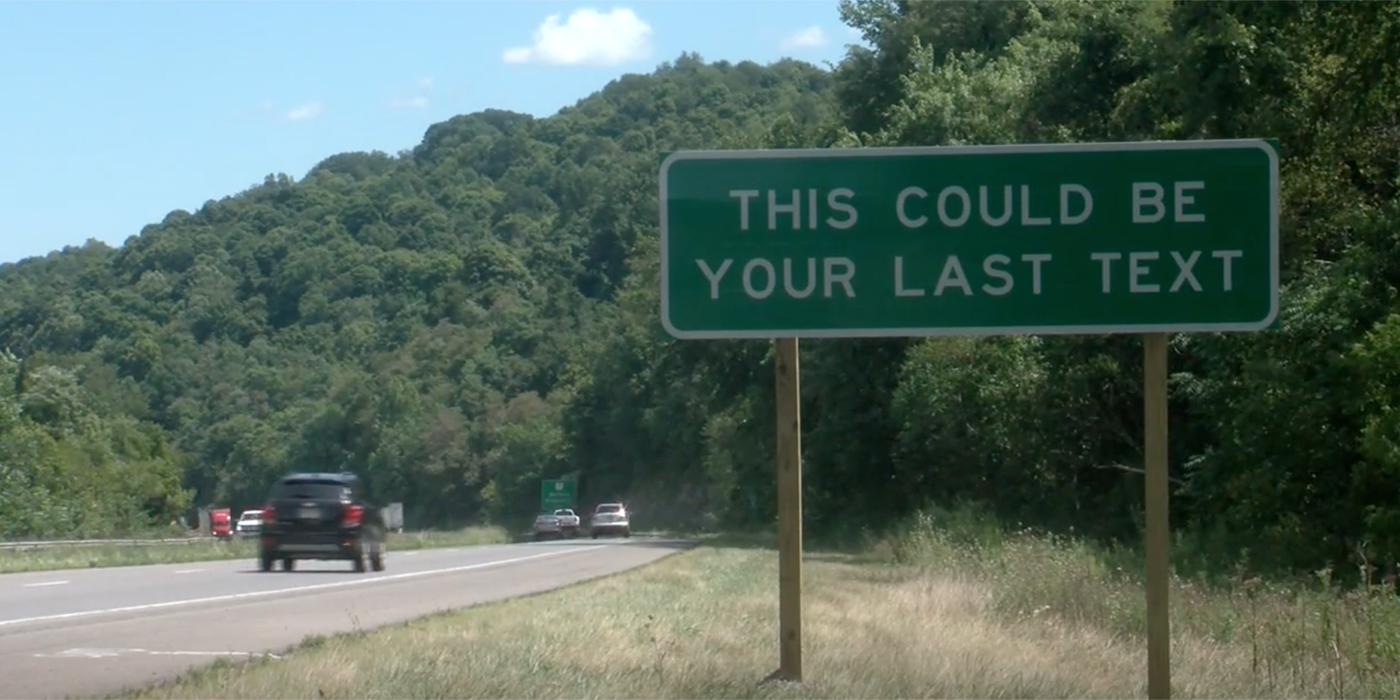

Another thing to keep in mind: If you don’t like paperwork, DRPs probably aren’t for you. Insurance companies document everything, so you’ll have a paper trail a mile long on one customer.

There are some simple ways we make the process a little easier on those who work in the shop and are our direct contacts for our DRP relationships. We’ve created “cheat sheets” for all our appraisers to quickly glance at when deciding how to write up a bid if they’re not sure of themselves. In addition, we recently hired a claim handler – a person to take the estimates and repair orders (ROs) from start to finish. And when the job is picked up, he then produces the final bill.

His job is to make sure we only charge some companies $2 for hazardous waste and some $3. He also checks parts on the bid, what was actually used, double checks to be sure the parts that weren’t used are removed from the RO, and that both the bid and RO say the same thing. He checks and rechecks the estimate for validity and to be sure we followed all guidelines. He also makes sure the customer has the money or makes sure we know who to bill.

Our claim handler takes a lot of burden off the estimators – who used to order parts in their spare time for jobs they booked. But because the estimators are sometimes so busy, they’d overlook things accidentally. That got us beat up by the insurance companies. The claim handler has solved most of these problems – things are running smoother and our technicians are getting the parts they need on time.

For us, it was easy to decide to hire this person. The volume of estimates and parts ordering was keeping everyone from figuring the bill. It may seem like a cost to our business, but adding this position has helped our CSI and has made our employees much happier. They like having parts to fix the cars on time. Also, our revenue has tripled, and we’re over a plateau. For months, we were stuck in a rut. Now, with the claim handler, we’re past that rut and moving forward again. There’s a cost for everything, but in this case, we also saw justified savings. Getting paid for what we did, and documenting it for everyone, including our customer, it isn’t a hardship now, thanks to our claim handler.

Steering to DRPs

So many shop owners talk about steering and forcing people to come to our shop because we’re a DRP facility. But this isn’t exactly how it works. The customer might have been sent to us for a bid, but no one is forcing him to book the repair with us.

We have posters in our estimating bay that say you can go to the shop of your choice. We also have pamphlets on the counter and displayed in different places in our office where customers stand or wait. We still ask for every repair. We don’t assume that someone is going to have us fix his car.

Also, if you listen to your customers, you can learn a lot. If a potential customer comes in and says his brother-in-law owns a body shop or his father owns a dealership, do you really think he’s going to be happy with the repairs from your shop? The hood could be so slick a fly couldn’t come in for a landing without sliding off, but this customer will likely pick apart your work, regardless. So it’d likely be safe to send him on his way now, and let his brother-in-law fix it. It saves you trouble in the end.

Granted, the insurance company may not be happy, but you just saved them “Excedrin Headache #51.” The insurance companies simply don’t know any better sometimes. And, in most cases, they don’t appreciate what you’ve just done for them either.

Most of the jobs I let go are people who wanted us to cheat for them. Everyone wants something for free. Some customers can tell you how much they’ve spent on insurance in their lifetime and are going to get it back on this $1,000 claim.

Over the years, I’ve found that 80 percent of my problems come from 20 percent of my customers. By eliminating some of these customers, I grow less gray hair. They can have a field adjuster look at it and then blame the insurance company later.

Producing Quality Work Despite Concessions

Over the years, I’ve read numerous articles and listened to many seminars about poor quality work dictated by insurance companies. Granted, we don’t always agree with the insurance companies’ methods, but that doesn’t mean my shop produces poor-quality work. That simply isn’t the case.

Some companies won’t let us figure blend time on the bids, and the only way they’ll pay for it is with pictures of blended, masked-off panels. And we all know almost everything needs blended.

Others won’t let us figure frame time on the bid. This causes two bad side effects: Say I’m the technician and I read the bid – no frame time – and I’m one of those people who likes having a goal to beat. You just took away my goal, and there’s no possible way to beat the time because it’s clock time. Also, the car could have been totaled if all the blend and frame times were in the original bid.

While this sort of stuff hasn’t stopped us from fixing cars properly, it does create more paperwork for the claim handler at the end.

Critics of DRP shops say that we don’t put the vehicle owner first – and that quality suffers because of this. I disagree. For example, we tell a customer that we agree, in many instances, that aftermarket (A/M) parts aren’t as good. And then we ask him how he’d feel about used parts. We look at three salvage yards, and if we can’t find used, we go new. We then document these facts and finish the bid. If the customer won’t accept used parts when we find them, we usually turn the job into a field assignment. This is an insurance-company policy issue – not our fight.

We consider both the vehicle owner and the insurance company our customer – with us as the third leg of a triangle. We have the trust of the vehicle owner and we’ll fight for him. We also know insurance companies aren’t the enemy and need to get along with them.

It’s a Business Decision

Many shops brag about how great it is to not have to answer to insurance companies and to have total control. However, we’re actually in control of our work, and we also have the trust of our DRPs. What more could we ask for?

Many body shops want to become DRPs for the wrong reasons. I hear my competitors saying: “Give me that DRP, and I’ll be able to cut a fat hog like you.”

Wrong, greed or trying to cheat the insurance company will get you nowhere.

On the flip side of that, some of the DRP deals are so bad that I don’t know why people take them. There’s only so much you can give. I know of shops that jumped on two DRPs we dropped. Neither would come up to semi-real rates. One wanted a $10 per hour concession on labor and 10 percent on all parts. The other one wanted $16.00 off the rack rate and only A/M parts. And by the time you finished the job, you were dealing with a new adjuster because the last one quit. Just to say you have a DRP arrangement is the wrong reason to be a loser. It’d cost less to stay home and watch Oprah!

Then there are those shop owners who talk in public about not wanting DRPs. Yet those same shop owner are calling the insurance companies to see if they can smear some other shop and get its slot. And if they can, they’ll do it in a New York minute. These shops will never make it as DRPs. You have to earn the right.

Once you’ve earned it – and the opportunity presents itself – then, at that point, becoming a DRP partner is strictly a business decision.

We look at all the contracts with our DRPs, and since we’ve been with Allstate so long now, we know what works and what doesn’t. For example, are labor rates, paint and material fees, discounts going to be user-friendly?

Insurance companies don’t want you to lose money. It’s not good for anyone when that happens and usually, with some reasoning, we can come to a fair and profitable agreement. We haven’t used an attorney with these contracts, but I think it’s a good idea to consider it now – considering that some insurance companies are now trying to transfer full liability onto the shop. Some now want certificates of insurance showing them as loss payee. If a repair goes sour, they go after our insurance for reimbursement. And we’re on our own.

Still, despite the challenges, all of our DRP arrangements are working for us. We’re profitable – and we have been for 29 years.

Sometimes, we have to look behind the agreement to see if the insurance company cares as much about their customers as we do. If they’re just number crunchers, you’ll never make money. All I have is customers and employees, my two most valuable assets. If an insurance company is just wanting less paperwork and someone to dictate to, it’ll never work. You need to look at the big picture and decide for yourself if your employees are efficient enough to work on multiple tasks and turn out quality.

If a DRP comes a-knocking at your door, you’ll also have to know if you can live with as high as a 6 percent reduction in labor and 10 percent on domestic parts. Of course, you have to average your rack rate work with the new discounted rate. Say it’s now a 3.5 percent reduction overall when adding 20 percent volume. If you’re only making 10 cents on the dollar, 3.5 percent would seem too high. I say a minimum net profit before averaging needs to be 12 to 15 percent to stay profitable. Some people might make it work on less, but it becomes harder and harder to get it back.

If you do get into an agreement and see it’s not working, almost all have a 30-day cancellation clause. Get out before you can’t afford to get out.

If you choose not to participate in DRPs ever, that’s your decision. But I have to ask that you stop criticizing those shops that do actively pursue that 20 percent increase in business volume.

What’s a Customer Worth to You?

I recently read that DRP shops will be sorry when the insurance hatchet comes down on our necks. I’d have to disagree with that statement: There will be life beyond DRPs.

I do, however, believe that DRPs are winding down, along with a slowing of consolidators and big multi-shop independents. Who knows? Someday, we might be writing competitive bids again.

When the stock market makes a comeback, insurance companies won’t care so much about saving because they’ll be making money on their investments. And someday, some states just might pass legislation that makes DRPs illegal.

So, if and when that hatchet does fall, my shop will have one thing that others won’t – customers who keep coming back for years to come, thanks to our exposure through the DRPs we’ve established.

After 20 years with Allstate, we’ve gotten a repair through Allstate and, later, after the customer leaves Allstate and goes to another insurance company, he returns to us for his next repair. My customers become my customers.

I had a customer named Henry who came to me 28 years ago. Ever since then, I’ve fixed Henry’s car – year after year. You see, Henry had five daughters. Just last year, Henry brought his 16-year-old grandson into the shop and introduced him to me.

“Son, this is where you bring your car,” Henry said.

That remark makes being a body shop owner seem all right, and it makes me feel about 10 feet tall.

You see, all these customers belong to me now. I value them. I know what a customer is worth.

As for you, when faced with the business decision regarding DRPs for your own shop, you need to ask yourself, “What’s a customer worth to me?”

Andy Batchelor owns Andy’s Auto Body of Alton, Inc. in Alton, Ill., and has been a self-employed automotive repair owner for nearly 30 years. He’s a certified Automotive Specialist with training from Rankin Technical School and a Platinum-certified I-CAR member, and has Master Collision Certification from ASE and a degree in Business Administration from Lewis and Clark Community College. Batchelor also serves as I-CAR’s Southern Illinois Training Chairman. Batchelor and his wife, Nancy, reside in Alton, Ill., and have two children, both married and living in the suburbs of Chicago.