For the 30 years I’ve been representing body shops and auto body repair trade associations, the “dollars times hours” formula has never made sense to me.

Charging an hourly labor rate for repairing a vehicle makes sense to me because if you know the costs of running your shop, you can figure how much you need to get per man hour to be able to pay your help, cover your overhead and make a profit.

Parts pricing also makes sense to me. You know what a part costs, and you can make sure the price you charge builds in enough of a profit to help keep your shop running.

But what does “dollars times hours” have to do with your costs for a paint job?

Shouldn’t there be something to factor in, depending on whether you can get away with using a cheap one-tone flat black paint or whether you have to use some exotic multi-tone specialty paint to match a particular color?

There are costs related to paint jobs that appear to be more similar to parts prices than to labor hours, yet the standard still seems to be (or has been until recently) to use a formula that considers only dollars times hours. With skyrocketing paint costs and increasing diversity in paint types, many shops are finally realizing there’s a problem and trying to do something about it.

But why has it taken so long? And what can you do to make sure you get paid an adequate amount for paint and materials?

More importantly, what can you legally charge and what is an insurer legally obligated to pay for a paint job?

Like every other part of a repair job, you can charge whatever you want for painting a car — unless, of course, you have a contract with an insurer that limits what you can charge. Otherwise, as long as you advise your customers in advance and get their authority for the work, you can set your own price, using whatever method you want to reach that price. You can use dollars times hours, you can use a complicated formula that figures the cost of the particular paint you’re using as well as how many hours it’ll take to perform the job, or you can pick a number out of the air. Generally, as long as your customer agrees to it, you can charge it.

And, indeed, this is the essence of the cost of both the ultra economical Maaco Ambassador Paint Service and

the ultra expensive paint job for that ’72 Vette restoration. In both cases, dollars times hours has little to do with the cost of refinishing. Rather, the shops charging for these paint jobs know very well what their costs are to do the jobs, and they also know what the market will bear, i.e., what their customers are willing to pay out of pocket.

Yet, the reality is that most paint jobs are paid for by insurers, and most of your customers don’t want to pay more than their insurers are willing to pay for a paint job. So, unless you’re a specialty shop, if you want to stay in business, you have to be willing to accept what an insurer will pay for refinishing.

But wait. Insurers are generally obligated to pay the “reasonable” cost of repair, and “reasonable” is supposed to be determined by what the market charges. But you are the market. Insurers should be paying what you — at least what the average you in your market — charges.

This makes what you can charge for the paint job (and, for that matter, any part of a repair job) similar to the chicken-egg conundrum. If you want to stay in business, then you must be willing to accept what insurers are willing to pay — yet insurers are required to pay the “reasonable” amount that you charge.

The Problem

Traditionally, the price of a paint job was figured by multiplying a chosen dollar figure by the number of hours anticipated to complete the job. This was originally based on costs for paints that were similarly priced, applied the same way and took the same amount of time to cover a given area. Under those circumstances, the dollars times hours formula might have made some sense. Assuming that the “dollars” part of the formula bore a meaningful relationship to the cost of paint in general, then the formula could usually yield a meaningful figure that would adequately compensate the body shop and allow the insurer a quick, simple way to figure its paint cost for any particular job.

Over the years, however, things have changed. A wide variety of paints are now available — specialty paints, specialty colors, various ways of applying paints, various layers of paints, etc. And the costs of all these different paints vary wildly. If the dollars times hours formula at one time yielded a relatively uniform, meaningful result, it would seem to me that it no longer does so in today’s world.

The Changing Standard

In varying degrees around the country, body shops, regulators and even insurers are recognizing that the traditional dollars times hours formula just doesn’t work any more. Paint manufacturers have helped by figuring costs of applying particular paints that they supply and disclosing the information to shops. They also offer a variety of products and training classes that help shops get paid more accurately. A variety of other guides and training programs also are gaining acceptance throughout the industry, such as the Mitchell Refinishing Materials Calculator (RMC), which works with any estimating system and provides accurate calculations for refinishing materials costs by incorporating a database of more than 7,000 paint codes from eight paint manufacturers.

In my state — the always ahead of its time and oh-so-politically-correct Commonwealth of Massachusetts — the regulatory board that licenses auto damage appraisers began recognizing the change in the nature of paints and their application way back in 1996, with a revision of its regulations. At that time, the board added what came to be a controversial standard, namely: “With respect to refinishing materials, if the formula of dollars times hours does not adequately reflect the cost of a particular repair, a published manual or other form of documentation shall be used.” While approved by both the body shop and insurance industry members of the board and while making great sense to me, the new standard sent shockwaves throughout the Massachusetts auto insurance industry, and those shockwaves continue to this day. In fact, as this article is being written, the licensing board is embroiled in a major lawsuit with the biggest insurer in the state over the enforceability and meaning of the standard.

The issues that have arisen in Massachusetts aren’t unique to the industry in this state; they exist throughout the country. How do you determine whether the traditional formula doesn’t adequately reflect the cost of a particular repair? What published manuals can be used? What other forms of documentation can be used? If two methods of determining paint and materials prices give differing results, which one should trump the other? If a guide only provides the cost of materials to the refinisher, is a markup justified in the final cost of the paint job?

In actuality, it doesn’t seem to me that these issues should be that hard to deal with. They’re similar to other issues that determine repair costs. Yet, insurers throughout the country continue to fight the use of anything but the traditional dollars times hours formula, and many continue to refuse to recognize the right of shops to make a profit on paint and materials.

I doubt that insurers are just playing dumb. It’s more likely that they’re doing whatever they can to protect their profits. After all, if they can get most body shops to continue to accept the old formula without a fight (or even with a fight), then why should insurers voluntarily change what they pay for paint and materials when that change is likely to increase claims costs?

What Is a Shop to Do?

Despite the resistance of many insurers, the door has been opened for body shops to get paid adequate amounts for paint jobs. Yet to this day, many shops still don’t understand this and still have to learn how to use their legal rights to get what they deserve.

So what should a shop do?

First, as with any part of a repair job, a shop should figure its actual costs for utilization of paint and materials.

Do you know what your paint costs are? Do you know what your materials costs are? Do you know what it costs to mix paints, if necessary? Do you understand the application process? Do you know how much materials loss there is in the application process? Do you know how much paint is needed to cover a particular area? Do you know how much labor time is needed to cover a particular area? If you can figure all of these things, then you can know where to start. To help you out, computer programs now exist to figure your actual costs in your shop for each particular paint job.

Another way to approximate what your costs are is to use paint and materials guides. The publishers of these guides have done studies, and supposedly the guides reflect actual costs and/or appropriate charges for various painting functions. Paint manufacturers have their own guides. Mitchell has a guide. There are many resources out there. It’s still advisable, however, that the best indicator for your cost is what you calculate it actually costs you to apply a particular paint to a particular portion of a particular vehicle.

Once you’ve figured your actual costs, you can figure what you need to make as a profit in order to charge the appropriate amount for applying refinishing materials. When you figure that, you can start entering it on your appraisals and start using it when negotiating with insurance appraisers.

Negotiating with Insurance Appraisers

As with all aspects of the repair, how you negotiate paint and materials depends on the particular insurer, the appraiser you’re dealing with and the nature of the individual you’re dealing with. Does this particular insurer have a hard-and-fast rule as to how its appraisers must figure paint and materials? Does your state have any statutes or regulations that control what appraisers must do in the negotiation process? Is the Mitchell Paint and Materials Guide or some other guide or system used with any regularity in your area? How bright is the particular appraiser you’re dealing with, and does he understand what the actual cost for paint and materials is for a particular job?

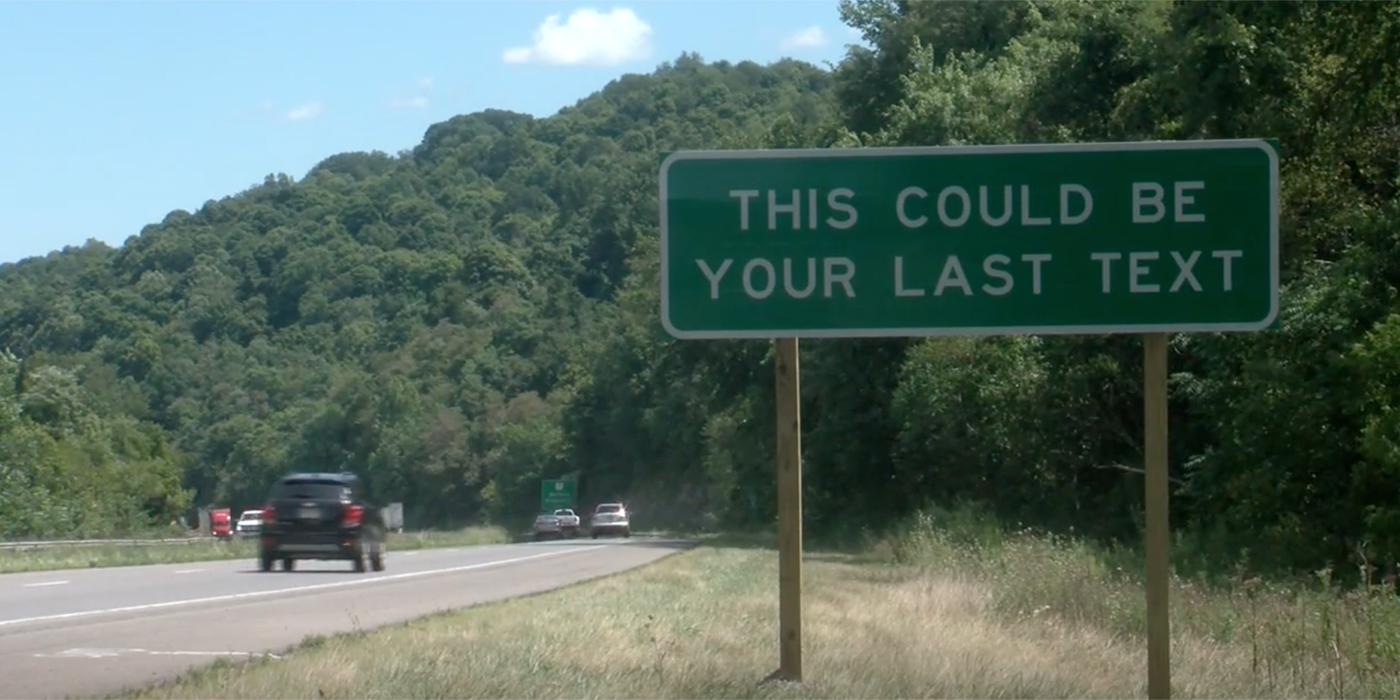

Can you get an insurer to pay what you need for a paint job? You’ll never know unless you ask, and you have to ask with some authority.

Whatever the circumstances, be prepared to demonstrate your actual costs. Whether you’re using a paint and materials guide, a manufacturer’s guide or your own documentation, you have to be able to give an appraiser some justification as to why the dollars times hours formula shouldn’t apply and why you have to get what you’re looking for.

If you’re not going to accept, “That’s all I can pay,” then you have to be able to justify, “That’s what I have to get.”

The purpose of the whole appraisal process is that a fair figure be negotiated between the insurance appraiser and the body shop appraiser for all aspects of a repair job. And, certainly, that should apply to paint and materials as part of the job. What should result is the “reasonable” cost of repair. But that’s not going to happen unless you’re prepared to demonstrate what’s “reasonable.”

In the process of trying to get paid a fair price for paint and materials, don’t forget that insurers are in business to make money. They have little incentive to pay more than they have to pay for a particular job because that’s going to increase claims costs and reduce profits. On the other hand, don’t forget that insurers are required under their insurance contracts and by law to pay the reasonable cost of repairs, so they do have to pay what the market charges. Failure to market cost could subject an insurer to being sued for violation of consumer protection statutes or could subject it to penalties being imposed by a particular state’s insurance commissioner.

Body shops cannot conspire together to utilize a particular manner of determining the price of a paint job, but no law can prevent them from becoming educated. If enough shops are educated as to what their true paint and materials costs are, things will change. If enough shops do an analysis to determine their actual costs for refinishing materials, they’ll learn what they have to charge as a fair price to paint a car. If enough shops then charge a fair price — with an adequate profit built in — then insurers will have to start paying that amount for paint jobs, or they’ll be breaching their insurance contracts and breaking the law.

Many shops seem to be getting the idea, but more shops need educated.

And never forget who your true customer is: the vehicle owner. If you’re not making much headway with an insurer, try talking to your customer. Perhaps the customer would be willing to pay the difference between what you’re charging and what the insurer is allowing (you never know until you try). Or perhaps you can educate the vehicle owner on your true refinishing costs, and he’ll go to bat himself against his insurer.

Time for a Change

In today’s world, the dollars times hours formula makes less sense than ever for figuring a charge for refinishing functions. Yet many people in the insurance and body shop industries continue to cling to this outdated manner of determining the price of a paint job. The door, however, has been opened wide to a new, sensible way to figure the price of painting a car. For body shops, it’s time to walk through that door and see what’s on the other side.

Writer James A. Castleman is a partner in the law firm of Paster, Rice & Castleman in Quincy, Mass. He has represented auto body repair facilities and auto body trade associations for over 30 years. The above article is an expanded and updated version of an article that appeared in the Damage Report, a publication of the Massachusetts Auto Body Association.

|

Start with Your Paint Company

Your paint company can help you bill more accurately for paint and materials — and get paid. All you have to do is ask. For example, if you have a mixing system, talk with your paint supplier about the ability to create invoices for the material you mix. You can use those invoices to negotiate with adjusters based on the actual cost of materials by the amount of the mix, the color code and whether the finish is a single stage, clearcoat or a tri-coat system. Most of these systems allow you to track the actual cost of all materials used in the repair. There are shops out there successfully using these systems to bill insurance companies. Also ask your paint company about training. The major paint companies have spent millions of dollars on “value-added” programs that focus on shop operations, customer satisfaction, business generation, insurance company relations, getting paid for paint and materials and more |