Whose role is it to set collision repair standards? Is it that of the third-party payer, the body shop community at large or, ultimately, your customers? While it’s true that he who holds the money is the final arbiter of standards, the behind-the-scenes bargaining with third-party payers has an awful lot to do with the results. Limitations on payment can’t help but affect the nature of repair work.

For these reasons, some believe repair standards are an insurance matter – although state regulators charged with monitoring the activities of insurers have, historically, wanted little to do with the regulation of body shops. Though this is slowly changing due to increased involvement in shop endorsements (“if this is where I was supposed to get my car fixed, then you must bear some liability for the results”), the guidelines set by even the most diligent regulators are ambiguous at best. Take the State of California’s Bureau of Auto Repair (BAR) for example, which has taken an unusually active role in the oversight of collision shops and actually has a code (Code 3365) for auto body and frame repair that reads:

The accepted trade standards for good and workmanlike auto body and frame repairs shall include, but are not limited to, the following:

A) Repair procedures including but not limited to the sectioning of components parts shall be performed in accordance with OEM service specifications or nationally distributed and periodically updated service specifications that are generally accepted by the auto body repair industry.

B) All corrosion protection shall be applied in accordance with OEM service specifications or nationally distributed and periodically updated service specifications that are generally accepted by the auto body repair industry.

Still, the BAR is reluctant to set a standard and defers to an ambiguous “generally accepted” standard, which in many cases, is no standard at all.

“When I question BAR reps about standards, the answer is that I-CAR is the accepted [standard] by the autobody repair industry,” says Rocco Avelini, former Southern California shop owner turned consultant. “But the BAR has no ability to penalize shops for improper repairs. As stated by one BAR rep, ÔThe only thing we’re here to do is to make sure that the repairs were attempted and that the items on the RO done and parts changed.’ “

Such ambiguity prevails on the East Coast, too. The New Jersey law says: “If the insured’s vehicle is repaired at a repair facility whose name is furnished by the insurer under above for a sum estimated by the insurer as the reasonable cost to repair the vehicle, the insurer shall select a repair facility that issues written guarantees that any work performed in repairing damaged vehicles meets generally accepted standards for safe and proper repairs.”

“Obviously, these words mean nothing other than what consumers are willing to accept, and each one is likely to be quite different,” says Charlie Bryant, a New Jersey auto body consultant and consumer advocate. “I’d be delighted to see standards that have to be met in the collision industry. [The term] commercially acceptable is [one] that allows much to be desired and actually appears to allow for less than proper repairs.”

But whose role is it to set such standards? The insurance industry doesn’t want to. The OEMs don’t want to.

I-CAR doesn’t want to. Even repairers don’t particularly want to.

This lack of standards – compounded by the insurance industry’s constant belt tightening around shop profits and, in many cases, unethical repairers out to make a buck any way they can – has actually given birth to an entirely new industry that thrives on exposing substandard repairs: post-repair inspections.

But focusing on shoddy repairs after the fact isn’t necessarily the solution. The damage already has been done. If, however, someone stepped up and held repairers accountable for the work they put out, many poor repairs could be prevented – rather than exposed.

Ultimately, it looks as if that someone is going to have to be consumers. The group of people most ignorant about the repair process seems to be facing the monumental task of determining when repairs are acceptable – and when they’re not.

How on earth has it come to this? And what role should repairers play in the creation and execution of these standards?

Different for Us

In other trades and professions, there are codes to which practitioners must conform. And they’re very clear cut. Household electrical wiring is either up to code or it isn’t. Plumbing and waste-management systems are closely regulated due to their effect on public health. Either a septic system “percs” or it simply isn’t a septic system.

The body shop business, on the other hand, is largely unregulated in spite of the enormous potential safety hazards involved in the repair of accident damage. Collision repair practices are based on a random set of events and subjective judgment calls. Different cars, different hits, different shops and different levels of training and expertise make it so. What’s more, differing sets of expectations among consumers also affect outcomes.

Consumer expectations have a major bearing on customer satisfaction indexing (CSI). CSI, however, isn’t to be confused with standards for repair. Satisfaction deals with an uneducated and unsophisticated person’s perception of the work performed on his car. The finer points of welding, surface preparation, body alignment and frame repair are essentially invisible. So as critical as CSI is to both insurers and repairers, it’s a mistake to hold customer satisfaction out as if it were some measure of how well you repair cars. If, for example, your shop winds up in court defending against charges of negligence, your CSI rating or all the customer endorsements in the world won’t save you.

I-CAR’s Vice President Thomas Mack puts customer satisfaction in perspective this way: Some consumers possess what he refers to as “perfect knowledge” of a product. For example, a consumer of candy bars has perfect knowledge of the product he’s eating. He knows what a chocolate bar with almonds is supposed to taste like. Very few consumers, however, can judge a body repair, save for cosmetic factors.

“We’re in an industry in which a consumer doesn’t have perfect knowledge,” says Mack. “In fact, we’re way at the other end of the spectrum.”

But customer satisfaction is the first standard you must meet, and since today’s customers are getting smarter all the time, attaining that level is getting harder. Though this is a business that deals primarily in appearance, it’s what’s under the shiny paint that really counts. The point is not to give a customer reason to suspect there’s something awry beyond that.

If things do go wrong, however, you’d also be wise to be sure your repairs meet “industry standards.” Despite the lack of formal written standards for completed proper repairs, almost everyone in this business knows the difference. It’s kind of like pornography … hard to define, but we all know it when we see it.

“We spent a million dollars putting the Uniform Procedures for Collision Repair together, but there seems to be a lack of interest in standards,” says Mack.

But I don’t believe there’s a lack of interest. Many in this industry would like to see an end to the bottom feeders who consistently turn out substandard workmanship. And a written standard goes a long way toward that goal.

The body shop business is like others in that there are competent and incompetent, ethical and unethical operators. Naturally the competent and ethical shop owners would like to see the others go away. But the fact of the matter is that there will always be those who take advantage of the unsuspecting. This is a fact of life and isn’t exclusive to the our industry. Bottom line: We can’t expect all repairers to police themselves. It just won’t happen.

It Is Written

Inasmuch as I-CAR shies away from the role of standard bearer, the fact remains that the organization’s repair model is referred to most often as a standard. It’s the closest thing we’ve got. Still, I-CAR insists that they don’t set standards and that their mission is limited to that of training technicians.

“I-CAR doesn’t define Ôstandards’ of any kind,” says Rick Tuuri, immediate past chairman of I-CAR. “I-CAR is a training organization and doesn’t Ôcertify’ technicians or establish repair standards. They train to provide the knowledge required to perform a safe and complete repair. They don’t follow-up, re-inspect or certify technicians or repairs in any way. That being said, I think that repair standards are de facto in nature and are really established by a combined effort of [insurers, consumers], OEMs, paint providers and maybe a couple more entities that don’t readily come to mind.

On second thought: “OEMs publish repair procedures [but] don’t really define Ôstandards’ either,” he says. But since these repair procedures are the closest thing the industry has to standards, “I-CAR always refers the collision repair professional to the OEM procedures as the best and only really specific procedure for vehicle repair. Even in I-CAR’s [Uniform Procedures for Collision Repair], the OEM procedure was always cited and listed as paramount in the repair process.”

Yet standards tend to develop with standardized training, which is precisely what I-CAR provides. But in order to do it by the book, there first has to be a book.

I-CAR’s Universal Procedures for Collision Repair (UPCR) is, by far, the most extensive and detailed publication of non-brand-specific body repair procedures ever published. But, as Tuuri points out, “The name UPCR was carefully chosen because it refers to procedures, not standards. This was the result of lengthy discussion and debate.”

UPCR began life as a commercial venture (a self-funding research and development project of traditional and emerging repair technology). But body shops didn’t bite. They didn’t even take a nibble – that is, until I-CAR backed off the commercialization part. Now the UPCR Web site is at 10,674 hits and counting, and is a place where techs have free access to the detailed procedures and can download a PDF file with text and illustrations.

“With our UPCR, we put together essentially what we were hoping for – guidelines of what to do,” says Mack. “The idea was that these would be the proper steps to do that repair.”

The idea, however, didn’t work out exactly the way they’d planned. “We were disappointed,” says Mack. “The shops said, ÔWe’re not going to embrace it if the insurance companies aren’t going to.’ “

But insurers did embrace the procedures. In fact, none would argue that the procedures weren’t the best practices. This, however, didn’t mean they were willing pay for them a la carte.

The insurance industry would have us believe that the UPCR comes with the repair the way washing the kitchen utensils and cooking the food at a restaurant does (included in the price of the meal). And in its attempt to differentiate price and procedure as separate aspects of claims settlements, the insurance industry has caused a good deal of cynicism within the industry toward I-CAR, while charges of hypocrisy have been leveled at insurers that support I-CAR.

The Market Determines Both Pricing and Standards

Repairers’ cynicism toward the UPCR came about when insurers refused to pay for the procedures. And why should they pay? Payment is based on market conditions only, which means items like a pre-wash or a test weld aren’t necessarily compensatible in terms of a claim settlement. It’s a matter of whatever a consumer can buy an acceptable repair for. And the term acceptable is subject to interpretation. What’s acceptable in the Bronx might not fly in Greenwich, Conn.

Prices are subjective and differ from shop to shop, from market to market and from insurer to insurer. Whereas one shop may not write for a line item, such as a destructive weld test, their estimate’s bottom line for the same repair may be higher than one that does include that procedure. Insurance adjusters tend to be short-sighted in this regard. If the bottom line is high but the adjuster won’t catch hell from his supervisor for paying what’s been deemed an unacceptable procedure with respect to pay, the shop owner would be more successful if he were to leave that procedure off the sheet.

Insurers rely on competitive local markets to define both pricing and standards, which are two separate components of the claim, according to them. So as insurers moved to micromanage the repair, in which each task became a separate line item, a corresponding payment was implied. This is why shop owners were at first enthusiastic about the UPCR. It seemed like the proper path toward payment for their services.

Bad assumption, it would seem.

As it’s been revealed in the now-famous State Farm aftermarket parts litigation, standards often can be a matter of what an insurer is willing to pay for; dollars control results. That is, when an insurer limits prices to that of substandard parts, the repair is equally substandard. The same argument is used by some repairers with respect to defective workmanship, i.e. had they been paid more money, they would have done a better job.

So does this mean that payers inherently control repair standards? State Farm Insurance Company spokesman Dave Hurst says no. “The market is defined by our participants,” he says.

Yet State Farm does have a standard for the repair of their policyholders’ cars. “Our Service First and Select Service shops agree to return our policyholders’ and claimants’ cars to their pre-loss condition relative to safety, function and appearance,” says Hurst.

This tells me that State Farm is very clever. You couldn’t ask for a better standard than that. It places the burden directly on the shop and relieves State Farm of the minutiae of enumerating the steps toward that end. In other words, “we don’t care how you do it, as long as the car meets the aforementioned standard.”

How Bad Will It Get?

For many, standards are situational. That is, what’s permissible in the repair of a 10-year-old Toyota may not be on an identical 2002 model of the same make. For example, some repairers and insurers feel color sanding and polishing is only required on newer cars, as opposed to one that’s six years old. What’s wrong with that assumption is that the two collision repair customers are likely paying the same premiums for collision coverage. Furthermore, if the contractual standard in their policy is that of pre-loss condition, this dual standard in claims would lead them to wonder if their cars’ OEM finishes suddenly got loaded with dirt.

To make matters worse, insurance companies with a penchant for lesser quality body parts also will set the line of demarcation based on the age of the cars. So a five-year-old Acura might not get a claim paid as thoroughly as that on a one-year-old Hyundai, even though the Hyundai’s OE build quality will never come close to that of the Acura. Yet claims personnel make their distinctions in such arbitrary ways.

Where do standards bottom out? Personally, I think we’ve hit bottom already. The automotive industry – particularly car dealers – generally won’t appreciate shoddy repairs in terms of what they buy. And people eventually sell or trade their cars, which is where the buck stops.

Dealers can’t, in good conscience, put poorly repaired or unsafe cars on their front lines anymore. Lemon law firms routinely pop dealers for these types of fraudulent practices. Furthermore, there’s a growing number of individuals and shop operators involved in post-repair inspections. Hackers can’t hide their misdeeds in market areas where these inspectors work. So the combination of the dealers’ heightened standards for trade-ins and the consumer-based appraisers such as Wreck Check and others are helping to turn the tide.

“Others” include an Atlanta-based start-up calling itself Network Information Communications (NIC), an outgrowth of the controversial Wreck Check, Inc. NIC has introduced the Seven Levels of Repair (SLR) – graduated levels of repair work based on how poorly the work was done, with corresponding levels of diminished value (DV) assigned.

What sets the NIC levels apart from the I-CAR UPCR is that the SLR deal only with outcomes, as opposed to step-by-step processes that take place before the car is delivered. Still, this is a significant departure from anything we’ve seen so far in terms of auto body repair standards. It does, however, fall somewhat short in terms of an authoritative repair code modeled after those in, say, the building trades. Instead, the SLR standard dwells more on what goes wrong in repairs. Doing it properly isn’t as much of an issue based on the fact that their SLR top level (DV1) is described in only a half page of text.

What impact have post-repair inspections had on the industry -Êand on repair standards in general? To tell you the truth, I’m not sure. Sure, I’ve caused some headaches in my area for the shops putting out substandard work. But the fact is that the stuff still happens. There are only a handful of us, and I wouldn’t want to be so self-serving and egotistical to tell you that we’re making a difference. We aren’t. Perhaps we are on an individual basis, which is all I can hope for. I guess we are changing the business – one claim at a time.

So Who Sets the Standards?

Clearly, insurers aren’t going to drive the standards initiative to the extent that it’ll raise costs. But no one – not even an insurer – wins a race to the bottom. Contrary to what some would have you believe, no carrier wants to see an insured’s car butchered. The fallout for an insurance company can be very costly in terms of re-repairs, litigation and a sour taste left in policyholders’ mouths. And this means lost customers and, more importantly, no chance to recover losses paid out in the claims by way of premiums collected.

Still, the fact of the matter is that the insurance industry doesn’t want the job of body shop cop. They resist having to pay more than once for the same repair. This isn’t to say they don’t bear liability under first-party benefits for the re-repair of their insureds’ vehicles. Ultimately they do. But getting them to step up is another matter.

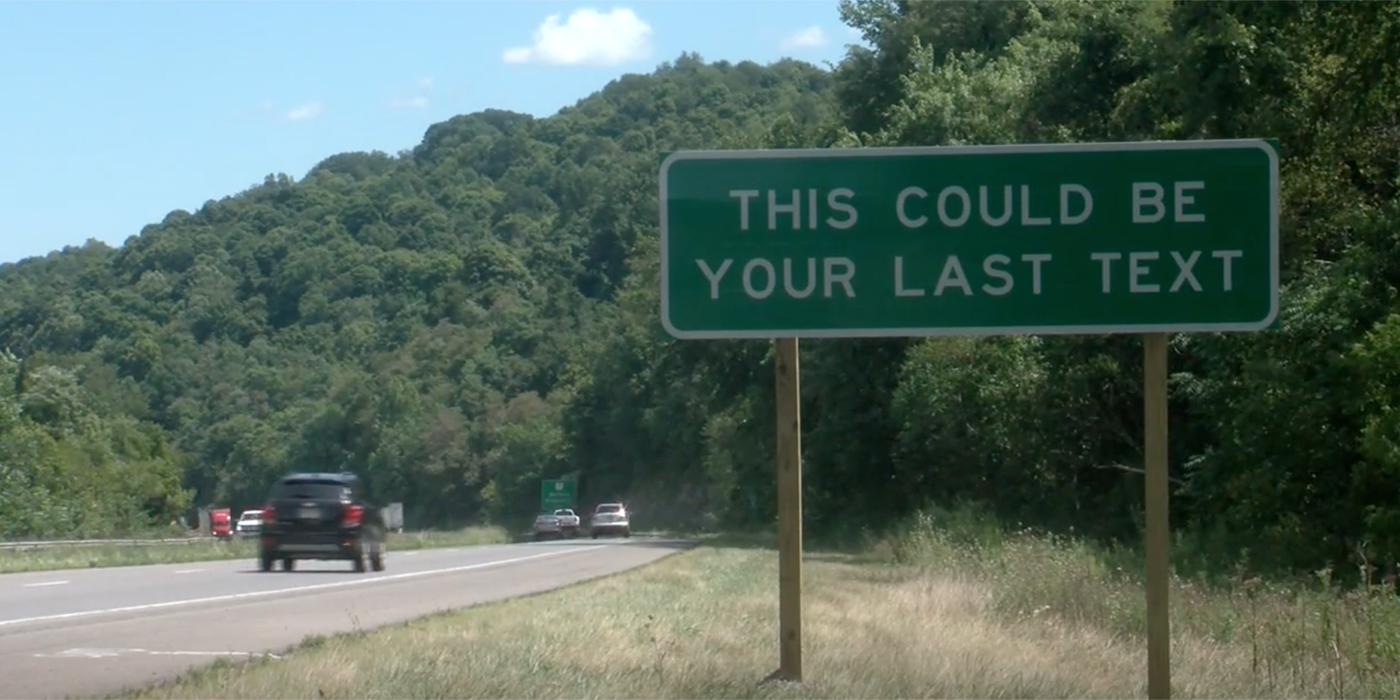

As many of us have come to learn, the buck always stops in the body shop. Substandard work erodes a shop’s CSI and devastates profits with redos and, in some cases, litigation. Let’s face it. Collision repair customers are becoming smarter (as well as more critical) than ever before, while insurance companies are continuing to do what they do best: lower costs.

This puts shops in a difficult position because, frankly, repairers simply can’t afford to put out perfect work. Because shops are working with a finite number of dollars, it’s not always commercially viable to do the best job possible. As a repairer, you’re under the gun to get things done so you’re often forced to ask yourself, “How good does it have to be? I can’t afford to make it perfect – not at these rates.”

To make matters worse, there are also clearly lots of repairers out there who simply don’t care. Some don’t care even when they get caught. And because insurance companies typically turn their back on the problems, the guilty face few repercussions in terms of future claims.

Though the responsibility for creating and upholding standards in the collision repair industry should be the job of repairers, each body shop can choose to raise the bar for quality work or to be a disgrace to the industry. What we’ve learned from some of the leaders in this business is that high standards and profits aren’t mutually exclusive. What we’ve also learned is there will always be shops out there that put out substandard work, which is why consumers get saddled with bearing the burden of setting standards.

“The customer (vehicle owner) has the Ôfinal say’ on all matters and is the final point of quality control,” says Tuuri. “No matter how good or bad a repair is, the consumer decides whether to accept or reject. He also decides whether or not he’ll continue to do business with his insurance carrier and the repair facility based on his experience.”

Helping to Shape the Market

So how can you make a profit and still live up to the standards set by consumers – a group of people who, for the most part, are completely ignorant regarding the repair process? By managing customer expectations.

Talk to your customers. Go over your estimate. And never say the car will be as good as new. A vehicle you repair may drive and appear like it did before – so that’s a safe thing to promise – but you can’t change the fact that the car has been in an accident.

“Pre-accident condition is, in my opinion, a poor choice of terms,” says Tuuri. “I prefer Ôpre-accident function and appearance’ for any number of reasons. For instance, true e-coat [electro-deposition primer] can only be applied by an OEM during the build process. The aftermarket can provide e-coat equivalent, which provides pre-accident function but not pre-accident condition.”

You also need to tell your customers the constraints under which you have to perform (the constraints being what’s humanly possible). You need to convey the fact that you can’t work miracles. Can a straightened unitized frame rail withstand another collision as if it were never hit? No, of course not. But it can be safe to drive a car like that once it’s been repaired. It’ll just be marginally less safe.

Constraints in terms of low-ball bids from insurance companies do not – and this is important – give a shop an excuse to turn out substandard work. This is the major point of contention between many in the industry. Some say it’s OK to butcher a car as long as the shop gives notice to the insurer and the owner prior to doing so. I say no. It’s never acceptable. If you can’t do a quality job, pass on the job. Sometimes saying no is all you need to do to get paid properly.

If an insurer suggests procedures or parts that you deem to be substandard, then you need to discuss this with the owner. It’s the owner’s decision what to do – and if there’s a fight, it’s the owner’s fight.

The fact of the matter is that standards for collision repair are now – and always have been – driven by market forces. But because consumers shape the market, consumer awareness will be the driving force in setting standards for the body shop business. Use this to your advantage. Educate customers. Show them there is a difference between shops.

Writer Charlie Barone has been working in and around the body shop business for the last 27 years, having owned and managed several collision repair shops. He’s an ASE Master Certified technician, a licensed damage appraiser and has been writing technical, management and opinion pieces since 1993. Barone can be reached via e-mail at [email protected].