Aluminum isn’t new to the collision repair industry. It’s been used by automotive manufacturers since the creation of the automobile. The lower a vehicle’s production numbers were, the more likely it was for aluminum to be used in its manufacture. This was because aluminum was easier to form by hand in low production numbers and a lot less expensive than making stamping dies necessary for producing steel

body parts.

Most luxury cars in the early years used aluminum, some of them extensively. It was used in different forms, too. The 1925 Pierce Arrow had a cast aluminum body. The Model T Ford used an aluminum hood at one point.

So, aluminum isn’t new to this industry by any means. But how we repair it, the temper (hardness) and the method of welding that’s recommended for our industry is.

Of course, the welding of aluminum has been around for a long time, too, and in different forms: gas, arc, tungsteninert gas (TIG),

metal inert gas (MIG), resistance and other methods that aren’t commonly used in the collision repair industry.

I began welding aluminum more than 40 years ago using oxyacetylene and a flux-cored rod process. I eventually graduated to the TIG process, which produces a fine-looking weld that has good penetration and a low weld profile. Universally, in most industries and most welding processes, TIG welding is some of the finest achievable. In nuclear facilities where large, heavy-walled tanks (over one-inch thick) are being welded together, the initial welding process used for the root weld is TIG because of the initial superior penetration and weld quality. However, this initial weld is followed by MIG welding in order to fill the bevel and finish

the process.

I’ve used a TIG welder in my shop for more than 30 years. Comparatively, it has a wide range of capability at a relatively low cost. This was the personal objection I had to overcome when faced with replacing the TIG process with MIG: There’s just no way you can find a really good MIG machine that will weld thin, one-millimeter aluminum in an open butt joint (no backing) (see photo 1) for the price of a decent TIG machine. That was my dilemma, and the path I’m taking you down should be viewed as the observation of a shop owner who welds and not that of a theoretical Ph.D. metallurgist. So, I’m appealing to what I believe will be the practical minefield you will step into once you begin your search for a MIG welding machine capable of welding automotive

aluminum.

For me, it was a long and detailed search, and I’m hoping my experience will benefit you should you consider purchasing one.

Get a Demo

First mine in the minefield: beware the salesman who can’t weld what you’re going to weld.

Always get a demonstration, hopefully in your shop with the machine hooked up to your power source. We observed three different machines at a common location at a trade show, and none of the reps could get their machines to work properly. Not a good day for those three, but it shows that without a good machine, a thorough understanding of the process and the particular requirements of the industry you’re selling to, just plain salesman’s BS isn’t going to win

the day.

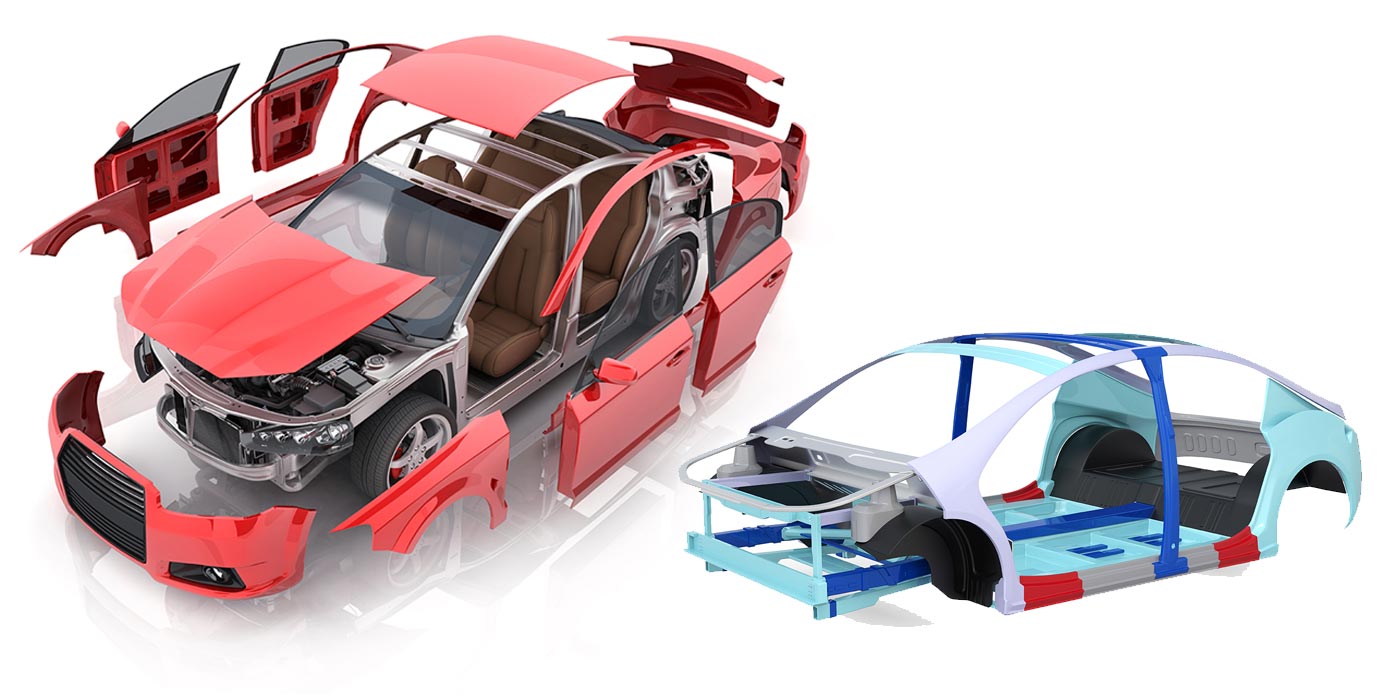

Always test the prospective machine on the thinnest material you’ll be working with, probably about one millimeter series 6000 aluminum. Save the hood or hatch from a Toyota Prius, a hood from a Buick, fenders or hood from a Ford Escape, or any other vehicle with aluminum parts (see photo 2) for the purpose of testing the prospective machine. This material is comparable to the lightest gauge and thinnest material you’ll be faced with.

TIG vs. MIG

The second mine in the minefield is price. I mentioned earlier the dilemma I had with my perfectly operational TIG machine and how it doesn’t cost what a MIG machine capable of welding thin gauge aluminum costs. Chances are you don’t even have a TIG machine now, and even if you were thinking about going

that route to save money, you’d be

stepping right on top of mine

number two.

It requires special skills to TIG weld that aren’t needed for MIG welding. If you can oxyacetylene-weld mild steel competently (doubtful), you could probably gain the TIG skill rapidly. You also have to incorporate the use of a foot pedal into the hand-eye coordination skills necessary (photo 3). So, the savings between the processes comes at a cost.

Let’s say you’re willing to cross that bridge and gain those skills. Fine, but there’s an additional hurdle to get over: No auto manufacturer recommends TIG welding on its cars. Why? There are a couple of reasons. One is because the TIG welding process is a high-frequency process. So? Well, listen to this…literally. Whenever I crank up my TIG machine to weld something, my wife, who’s in the office, tells me that when she’s on the phone she can hardly hear the person on the other end because of all the interference on the line. That high frequency generated by the TIG process turns every wire in the building into an antenna, including the phone lines, not to mention the wiring in the car you’re working on. The cars have many computers hooked to those wires, which can be potentially damaged. So, if you’re going to do some TIG welding, the part must be removed from the car. It’s time-consuming, but it can be done…unless, of course, you’re working on an aluminum-intensive vehicle like a Jaguar or Audi A8. On these vehicles, if the part is welded or riveted to the structure and the repair or replace operation requires welding, you’re going to be required to MIG weld.

The second reason not to go down this TIG welding rabbit trail is because it has the slowest deposition rate of any form of electric welding. That means the Heat Affect Zone (HAZ) will be larger than with MIG. Any form of welding on aluminum will anneal (permanently soften) it. So, if we’re doing structural welding on an aluminum-intensive vehicle, we want to keep the HAZ as small as possible to maintain structural integrity, a requirement that necessitates the MIG process.

So now you know why a MIG machine is sometimes preferable to a TIG machine. Many of the people you’ll be dealing with when purchasing a MIG machine won’t know this, so beware and always verify what you’re being told. Automotive collision repair and specifically collision repair welding is a miniscule part of the welding equipment manufacturing business. Consequently, equipment manufacturers’ knowledge of the requirements of our industry is miniscule. You’ll have to dig to get to a point of knowledgeable comfort and satisfaction.

Not the Same as Steel

Here’s your third mine. You’ve been welding steel with a MIG for years. “So what’s the big deal?” you ask. “Can’t I just convert my current machine and adapt it to weld aluminum?” You could convert your 220V machine to weld aluminum – check with your welding supplier. But it isn’t inexpensive and it’s

like a shot in the dark. What do I mean? Well, you’re not going to know until you purchase a spool gun and adapter setup and try it to know if it’ll work, but if you’ve got a spare grand and some extra time, you could give it a try. Or, you could ask your jobber to order what you need, help you adapt it and, if it doesn’t work, take it back and get a refund. I’d like to hear that conversation!

Here’s the deal: Your conversion will probably work on two-and-a-half millimeter…kind of. This is structural stock. When you try it on the one-millimeter body stock, you’ll have less fun, but don’t be discouraged. It isn’t you. That machine you bought for collision repair on steel cars was never intended to weld light gauge aluminum (see photo 4). It needs some additional engineering to be able to do this well.

Aluminum melts at around 1,200 degrees Fahrenheit. Steel melts at close to 2,800 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s way more than twice as hot. Aluminum also conducts heat way faster than steel, which affects the way a weld stops and starts. That can be engineered as a feature of a welder designed specifically for aluminum.

The machines I have in my shop for steel are constant voltage machines. They’re good 220V machines, which are capable of a wide range of work. They’re spray arc machines and weld .023 and .035 wires equally well…on steel. The machine I bought for both aluminum and MIG brazing is a three-phase pulsed spray arc. This means that the machine cycles rapidly from 110V to 220V many times per second. This is what allows you to successfully weld the thin gauge aluminum without a backing, but then, this welder was manufactured to do this, unlike trying to convert a welder that wasn’t engineered to weld aluminum. These are special machines and are significantly more expensive than a very good machine that you’re familiar with buying to work on steel cars.

Drive Systems

You’ll find a wide range of prices of machines that can do the job. I

know this because I’ve tried them and

priced them.

A .030 aluminum wire is soft compared to steel. Driving that wire through a conventional cable and liner to the torch is problematic for some manufacturers. Spool guns solve this drive issue of bird-nesting the soft welding wire by making the drive system, liner and welding torch as a single all-inclusive unit, right at the end of the cable. Small spools of wire and a liner that’s only an inch long (compared to 10 feet long) drastically reduce feed problems (photo 5). The tradeoff is a more bulky unit to handle in tight spots. However, this can save you some money. On the other hand, do you know of any high-production, aluminum-intensive vehicles built in the U.S.? Hmm…you’re catching my drift.

Yes, the Europeans have some sophisticated welders for sale. Some of them use the compact conventional torch on the end of a liner cable, which is every bit as convenient as what we’re currently used to for steel. These have sophisticated drive systems that have controls on the torch handle. Many have programs set up automatically for specific joints on specific cars within their factory preprogrammed data systems on board the welder. A simple digital code and you’re ready for a test weld. Cool, huh? You will, however, pay for this.

Training

Lastly, I highly suggest taking I-CAR courses

prior to making a purchase. I suggest courses WCA01, 02, 03 and DAM05.

If you’re interested in additional aluminum repair topics, look for courses STA01, PRA01, SSA01, SPA01 and SPA02.

There you have it. Hopefully, this will keep you from the pitfalls surrounding this issue. Choose wisely and be well.

Writer Mike West, a contributing editor to BodyShop Business, has been a shop owner for more than 30 years and a technician for more than 40 years. His shop in Seattle, Wash., has attained the I-CAR Gold Class distinction and the ASE Blue Seal of Excellence.

|

Questions to Ask Before Buying a MIG Welder

1. What’s the power requirement? (It has to be 220V). It may require three-phase. |