Evidence suggests that the current method of bookkeeping began in Italy, early in the 13th Century. The standard and accepted double-entry method of credits and debits, ledgers, balance sheets and income statements is as old as modern civilization itself. With an 800-plus year track record, these documents have come to represent the standard measurements businesses use to determine success. And this is why it will be so difficult for you to believe me when I tell you that it’s all wrong.

Well, it’s not all wrong. It all fits together nicely to record revenue and cost information about your business. The problem, however, is that most owners use that information as the measurements for the business — as a guide to improving the business.

Here’s why this doesn’t work …

Every business records its revenue by breaking it down into categories of sales. For example, we record the things we sell into mainly four different categories: labor, parts, materials and sublet sales. We record this way so we can break it down and understand the percentages of the things we sell – 48% labor, 9% materials, so on and so on. We also then record, by default, the cost of the things we sell in each of the same categories. This then allows us to measure our profit made on each. For example, for every $1 of labor sold, we spend .50 cents — or have a 50% labor profit (margin). So you can add up all the sales categories as well as the cost of each to determine the gross profit.

Makes sense, right?

If you’ve ever hired a consultant or asked an accountant for advice, the first thing they’ll generally do is ask for your financials. Why? Because this is the most accurate recorded information about your business available. After all, that’s why they call it a “balance sheet.”

Problem is, these aren’t the measurements of your business’ performance. They’re simply recorded historical information. It does, however, represent what you would like to see improve: the bottom line. So the natural tendency is to start with the financials and examine things like the individual margins, gross profit or overhead costs to see if changing them will improve the net.

And this is where it all begins to unravel.

OK, so let’s go through this typical cost analysis exercise. We’ll say your financials show that your gross margin is 38%, and your total overhead is 32% of the total sales. Your net has to be 6% (38 minus 32). So if I want more than 6%, say 12% net is my goal, I can increase the gross to 44% and I’ve got it (44 minus 32 = 12). Now my current 38% gross is made up of a 48% labor margin, a 29% parts margin, a 25% sublet margin and a 45% materials margin. You’ll also need to know the “sales mix” of each of these things in order to determine what the total gross profit is. Refer to Chart 1 above to see how this all looks.

Alright, I have several options to get that 38% gross to 44%. I can increase my labor margin to 62%. Or I can increase my labor margin to 55% and improve my parts margin and my materials by a couple points. I have many options. Check out Chart 2 above to see how I’d reach 44% if I used the second option.

Still makes sense right?

But it’s what happens next where the real damage is done. Someone will begin to independently determine how to improve the cost of one of these components in order to achieve the desired outcome. Why is this bad? Because the cost of a component is always subordinate to its effect on the overall. Not that the cost isn’t important. It’s just that it falls at most, second on the list of importance. But a financial statement will never show you that.

Here’s an example: Our accountant or consultant suggested that we can improve our parts margin to 34% from our current 29% by purchasing parts from several new vendors who offer a better discount. This will help to improve our overall gross profit by two points, getting us closer to our goal of 12% net.

So let’s say you go with that. You let everyone know, “Here’s who we purchase our parts from now.” But after a week or two, you realize that this new vendor only can offer you this discount because he’s cut his own costs.

Say, for example, he’s cut his delivery trucks down to one and reduced his counter help by two. All of a sudden, 20% of everything you order is coming in wrong, it now takes twice as long to get parts as it used to and you’re never confident of when your parts will arrive.

All of these parts issues are now consuming your management resources. Focus has shifted to addressing these parts problems. Next thing you know, where as you used to deliver 15 cars a week, you’re only delivering 14. Your parts margin is looking great at 34%, but what has happened to the net? See Chart 3.

You’ve improved your parts margin and your gross margin, but in doing so, you’ve decreased your NET! This is classic process sub-optimization (measuring independent

efficiencies).

Are you starting to see the danger in making improvement decisions based on your financials? Thing is, every young MBA consultant I’ve worked with in the past has always started here. It’s always the same analysis and always starts this way.

As I said earlier, because financial statements are the most accurate record-keeping that most businesses have and, ultimately, represent the end results or goal of any business (to make money), they’re often used as a roadmap to improvement. But they’re not the right measurements!

I’ve posed these scenarios to every consultant I have worked with in the past and always gotten a fairly blank stare back. Things like cost accounting and even job costing for us, while they may be a helpful tool, are by no means the measurements we need to look at for improving our business. The problem is that most businesses have no other measurement available, and many people make their living collecting, auditing and analyzing this information.

Here’s another, opposite example of why this sub-optimization doesn’t work. Let’s take the same scenario with parts: Your hired smart person suggests you use a new parts vendor to improve your profitability. But you realize that if you didn’t have to deal with all these current parts issues and could get parts faster, your resources would be freed up and you could probably get one more car out the door every two days (you’ve noticed how much time your techs are spending not fixing cars, but instead, dealing with parts problems).

So you look for a vendor that’s willing to double check every order you place and deliver them to your shop 100% complete in 24 hours. But in order to do that, he has to reduce your discount from 29% to 26%. Your hired smart guy is appalled at the suggestion of decreasing your parts margin, but something tells you that the cost of a component is subordinate to its effect on the overall business. So let’s say you do it and were right. Check out Chart 4 to see what happened to your business …

You lowered your parts and gross profit percentage but improved your net profit in both percentage and total dollars — all because the cost of a component is always subordinate to the component’s effect on the overall business.

You can do this same exercise with labor margin, materials margin, overhead salaries, you name it, and you’ll find the same possible scenario.

Changing (lowering) the cost of any of the components on your financial statement can have a positive or negative effect on the net. The problem is that you just don’t know until you do it, and often, the change has little or no effect on the overall.

You have to understand that individual efficiencies don’t matter. What good is a better labor margin if you only wind up building more inventory of work that you can’t deliver? What good is it to have a paint shop that can paint five cars a day, but body techs who can only build three cars per day? Only the overall efficiency of a business matters.

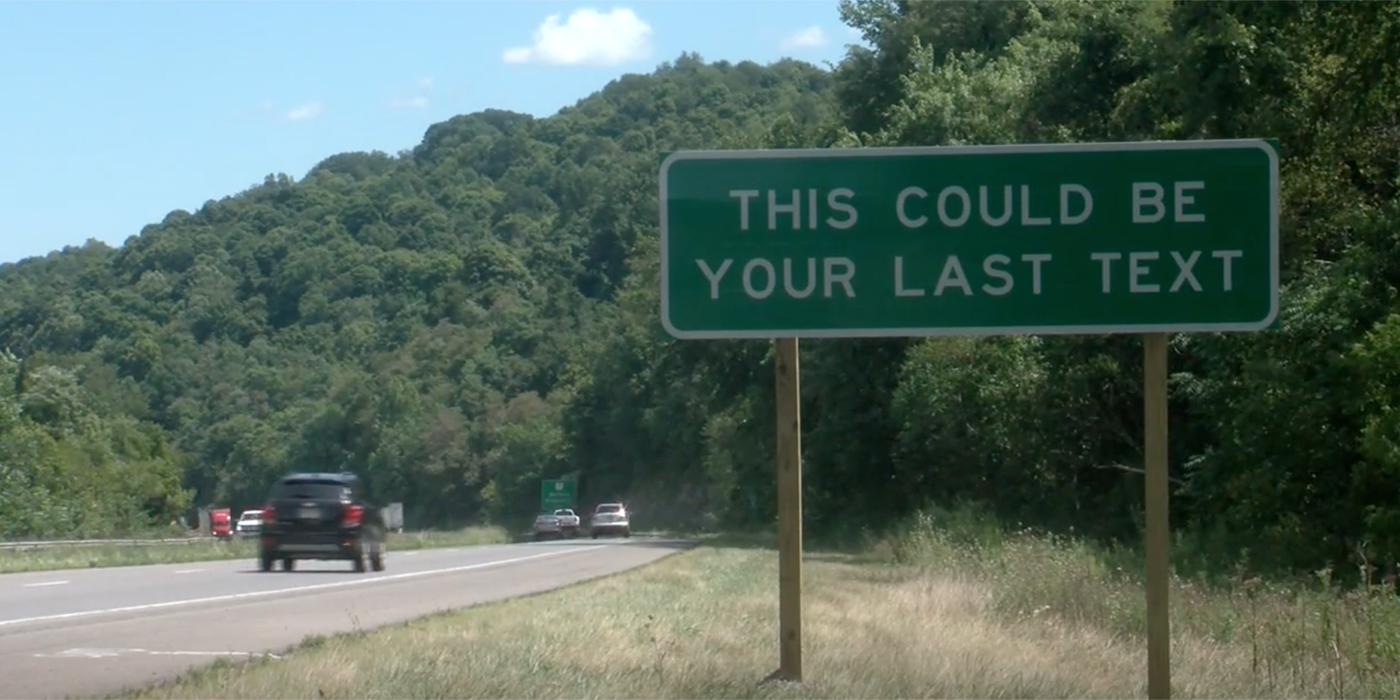

The only time we “Ring the Register” is when we correctly deliver a vehicle. We don’t make money on parts margin — the driver doesn’t hand us 30% of the list price of the part when he delivers it, does he?

Let me say that again: We only make money when we correctly deliver a vehicle. So then that’s got to be goal for the business.

So how do we deliver cars faster? That’s right, faster. The key is speed! Where on the financial statement does it show you your speed? That’s the real measurement.

If we could make our overall process more efficient so that every vehicle moved through it with less interruption, we could “Ring the Register” more frequently. If we kept our overhead cost the same and increased the rate at which we move vehicles through the business, we would make more money. So more important than focusing my time trying to improve the efficiency of individual pieces of my business (making localized improvements), I should focus my time on how the pieces relate to each other, how they work together.

If I can improve the relationship between all the steps, then the whole thing should work together more smoothly. It should flow.

The smoother it flows, the faster it starts to flow. And the faster it flows, with the same overhead cost, the more cash it generates. That’s where the real profit lies.

By the way, there are a whole lot of other benefits as well. If it’s a faster process, then your cycle time is greatly reduced (a good thing). And it can only go faster if there are less mistakes — if things are done right the first time — which means quality improves too.

You’re going to have to let go of a lot of what you held sacred if you want to be great. Don’t get me wrong. You can be OK minding your Ps and Qs in the traditional cost accounting sense, but you’ll never set the bar for the industry.

You’re going to need a new measurement, and it’s going to have to be related to how well the whole thing flows. And that’s what process efficiency is all about — how efficient the whole thing works together.

What will reflect the performance of how the steps of a collision repair business work together?

The answer is in creating flow, taking a systemic approach to your business. Creating an inter-dependent series of activities that allow you to see and measure the things that will lead you to world-class performance. What I’m talking about is a different method of managing and operating a business, not a new way to do the same old thing. A wholesale change in the way you think about things.

It’s not really a new method, but because of its counter-intuitive nature as described above, it’s rarely implemented. Only a small percentage of all industries go here, but in today’s economic environment, more and more companies are learning and implementing these principles. It requires a new, well-thought-out structure to your operations. The good news is that it requires little or no capitol expense to execute and delivers rapid and sustainable improvement.

For those of you who believe that a better way is both possible and required, stick with us. This is just the second in a series of articles for BodyShop Business that will help take you step-by-step through creating your own lean, process-centered business.

But before you can get cracking at making the change, you must understand some additional principles. Next month, we’ll examine “waste” — what it is, how to identify it and why you need to eliminate it.

I hope the subject of process efficiency vs. localized efficiency made sense to you. Please let us know.

See you next month!

Writer John Sweigart is a principal partner in The Body Shop @ (www.thebodyshop-at.com). Along with his business partner, Brad Sullivan, they own and operate collision repair shops inside of new car dealerships, as well as consult to the industry. Sweigart has spent 21 years in the collision repair industry and has done everything from being an independent shop owner to a dealership shop manager to a store, regional and, ultimately, national director of operations for Sterling Collision Centers. Both Sweigart and Sullivan have worked closely with former manufacturing executives from Federal-Mogul, Morton Thiokol and Pratt & Whitney in understanding and implementing the principles of the Toyota Production System. You can e-mail Sweigart at [email protected].

Comments? Fax them to BodyShop

Business editor Georgina K. Carson at

(330) 670-0874 or e-mail them to [email protected].