Industry consolidation is alive and well.

Even though all major players involved the consolidation of the collision industry have had their problems, the consolidation business model continues to evolve and improve, drawing more and more interest from consumers, the investment community and insurance companies.

Caliber Collision, with 62 body shops concentrated in Southern California and Texas, and Minnesota-based ABRA Auto Body & Glass, with 51 company-owned shops in several states (along with 17 franchise and affiliate body shops under the ABRA name), are the largest and arguably the strongest U.S. players having company-owned shops.

Tim Adlemann, ABRA chief operating officer and original founding partner, says ABRA is on a growth track to achieve 11 new greenfields (shops built from the ground up) and 10 acquisitions for 2002. But he admits ABRA had to overcome its share of setbacks over the past couple years, converting the large number of independently operated body shops acquired in the late 1990s into ABRA-branded facilities.

Because of this, Adlemann says that ABRA – along with other consolidators – generally had to slow down. The rapid pace at which they were acquiring shops during 1997-2000 made it difficult to integrate and standardize operations of newly acquired shops.

This integration issue has affected all the major players after the spending spree of the late 1990s. But the strongest players have learned from past mistakes, and shop growth is starting to happen again.

Although it appears that Caliber Collision is continuing to grow at a steady pace through the acquisition of new facilities, Bill Lawrence, Caliber’s COO, agrees with Adlemann that integration and standardization of operating systems are the biggest hurdles that consolidators have to overcome to maintain constant growth.

Lawrence recently said that Caliber’s goal is to open 30 new collision repair facilities a year. Though he made no distinction between acquisitions and greenfields, it’s clear his company leans more toward acquiring a proven body shop than introducing a new facility into a market.

Lawrence compared the expense, the investment, and the time to train, set up operations and develop new business-to-business relationships with acquiring a proven, reputable body shop that’s achieved a strong market presence and a solid operating system. It appears that after much trial and error, Caliber has honed its skills and all but eliminated past integration mistakes by using strict market and shop selection criteria, along with a detailed shop assessment process.

Despite this progress, it’s generally agreed throughout the industry that a national consolidator with a significant market presence in all major metro areas isn’t likely to emerge anytime soon. However, consolidators are continuing to learn from past mistakes and moving forward toward their goal of successfully shrinking the collision industry and monopolizing the profit pie.

What does all this progress mean to you? Will you be able to compete in the coming years? If so, how? Although the future is never entirely clear, it’s safe to say that yes, independents will be able to compete – as long as they keep up with consolidators price, service and quality offerings.

|

Exit, Stage Right And contrary to popular belief, the size of your operation doesn’t appear to make a difference. As long as it has potential, even a smaller operation can be an acquisition target. Lawrence noted that Caliber recently acquired a 5,000-square-foot shop doing $60,000 monthly. After implementing Caliber’s operating processes, the facility now is doing $200,000 a month. My record-best square footage producer (where I personally assessed the shop and its financials) is a 7,000-square-foot shop doing a little more than $250,000 monthly. |

Insurers Goals Fuel Consolidation

In an April 2002 Best’s Review article on autobody consolidation, “Best Friends,” Lynna Goch wrote: “Autobody shops, former symbols of mom-pop businesses, are evolving into streamlined networks and offering attractive cost solutions for auto insurers.”

Goch went on to say that “the seven or eight large consolidators doing business in the U.S. represent the cutting edge in technology, expertise and customer service, which is their draw for insurers.”

It’s true that insurers are continuously looking for better ways to manage the customer’s complete claim-repair experience. During my past life at Allstate, the company surveyed their policyholders and discovered those who had an auto-claim repair experience didn’t feel that their claim was settled and that Allstate was off-the-hook until the car was repaired to their satisfaction. Allstate responded by forming the first network of direct-repair provider body shops, which were willing and able to deliver what policyholders demanded: hassle-free claim-repair services.

The “Best” article reinforced what Allstate figured out long before other insurance companies: Insurers must try to control you, the repairer, because they’re scared of the downside of a bad repair experience. This is why insurers prefer to deal with consolidator body shops, which are strategically on the same page as insurers.

But industry consolidation isn’t just about the huge corporately managed and well-funded Caliber’s and ABRA’s. Consolidation is widespread. All the so-called independent operators who open a second, third or fourth store are also consolidating, or limiting the number of owner-operated body shops. I also classify an operator who replaces his existing operation with a mega-facility that does the volume of five to 10 average shops as a local consolidator. After all, if this shop is turning out $7 million or more annually from a single location, it’s essentially taking over a local market without having to build or acquire multiple locations.

And there are more shops than we think in the 20,000- to 35,000-square foot range that are turning out 400 cars a month. What if those shops went to double shifts and added maybe another 200 to 300 cars monthly? What if they went to three shifts, seven days a week and added 300 more cars a month? It’s hasn’t been done – yet – but it will be and when it happens, how many average body shops will a shop like that replace in a local market?

Market Fuels Consolidation

The collision repair industry is a classic example of a highly fragmented industry characterized by thousands of repair providers who deliver widely diverse levels of service. And consolidation is a natural economic evolution facing all industries where the consumers or buyers are searching and demanding improved value (price, quality and service) and investors are seeking to take advantage of high profit potential.

Except for niche markets, specialty products, regulated industries or products, and sometimes physically constrained markets (i.e. rural and urban areas), every service and product industry has experienced consolidation. Collision repair will be no exception. It would only take 3,500 shops doing $5 million or more a year to control 70 percent of the $25-billion-a-year insurance-claim repair market.

Sterling’s ultimate goal embraces this spirit of consolidation – however scary a thought it may be to independents. According to Sterling’s Web site: “Sterling is hoping to do for autobody what Staples and Office Depot have done for office supplies, Home Depot has done for home repairs and maintenance, Starbucks has done for coffee and Autozone has done for auto parts.”

As you likely know since you’re also a consumer, larger organizations are typically able to outspend smaller operations for training, research and development, technology and management talent. Usually, these investments create a competitive advantage through innovative service offerings, lower prices and operating costs, preferred supplier relationships and greater access to low-cost capital (loans).

Look at every product or service industry you can think of: food, clothes, cars, telephones, appliances, financial services, etc. Over time, each has gone from a highly fragmented industry of numerous suppliers to one that’s become consolidated with fewer providers. And consolidation continues until either the product or service becomes obsolete and is no longer demanded by consumers, or until the number of industry providers are so few that they begin to employ monopolistic tendencies such as increasing prices and reducing service levels – forcing regulatory actions to either break up dominant providers, install price and quality controls, or force better opportunities for new providers to enter and compete in the market.

What Consolidation Means to You

Except for rural or remote areas and specialty body shops that target high-end cars, consolidation is a threat to your livelihood – unless you’re able to deliver and compete with the best of the best. And even those who feel protected by focusing on Mercedes, Lexus, BMW and the like should still beware because large consolidators have the resources to enter these specialty segments whenever they need to.

If your shop is very profitable, basic economics tell us that someone will try to hone-in on your business. And when it comes to business, long-term or exclusive ties can be fragile if someone else comes along offering a better deal.

Consolidator groups who have cheaper access to capital than you will go after and acquire your unique, secure and profitable business segment whenever it makes good business sense for them to do so. Luckily, you still have time because there’s lower-hanging fruit that consolidators can pluck faster and cheaper, at least for the moment.

A Caliber press release on the recent capital investment in Caliber by The Interinsurance Exchange of the Automobile Club read: “Our scale enables us to control our costs better than the average collision repair business. This purchasing power, coupled with our broad market coverage and intense focus on customer service, positions us to provide best-in-class quality, service and pricing to our clients.”

Does this mean that it’s time for single-shop independents to throw in the towel because it’ll be impossible to compete? Heck no!

As a consultant constantly seeking new ways to light a fire under shop owners’ butts to inspire them to improve their businesses, consolidation is a good thing. Competitive threats are major motivators for providers in all industries to rethink their business strategies and to seek out innovative ways to improve their operations. Without competition, what would you have? An inefficient, wasteful enterprise.

Consolidators are service and cost focused, and they know how to negotiate a deal with insurers. Isn’t that how you got your business started and made it profitable? It’s not rocket science. The problem is that an independent operator is more likely to become stagnant, while consolidators never stop. They keep pushing and pushing – they’re under too much pressure to become complacent.

Consolidators are also cost-driven to improve efficiency, revenue-driven to improve throughput, and employee and safety focused. Some even conduct employee opinion surveys and rate employee satisfaction side-by-side with CSI measures. Because of Caliber’s focus on employees, Lawrence says they’ve only lost two A-techs in four years.

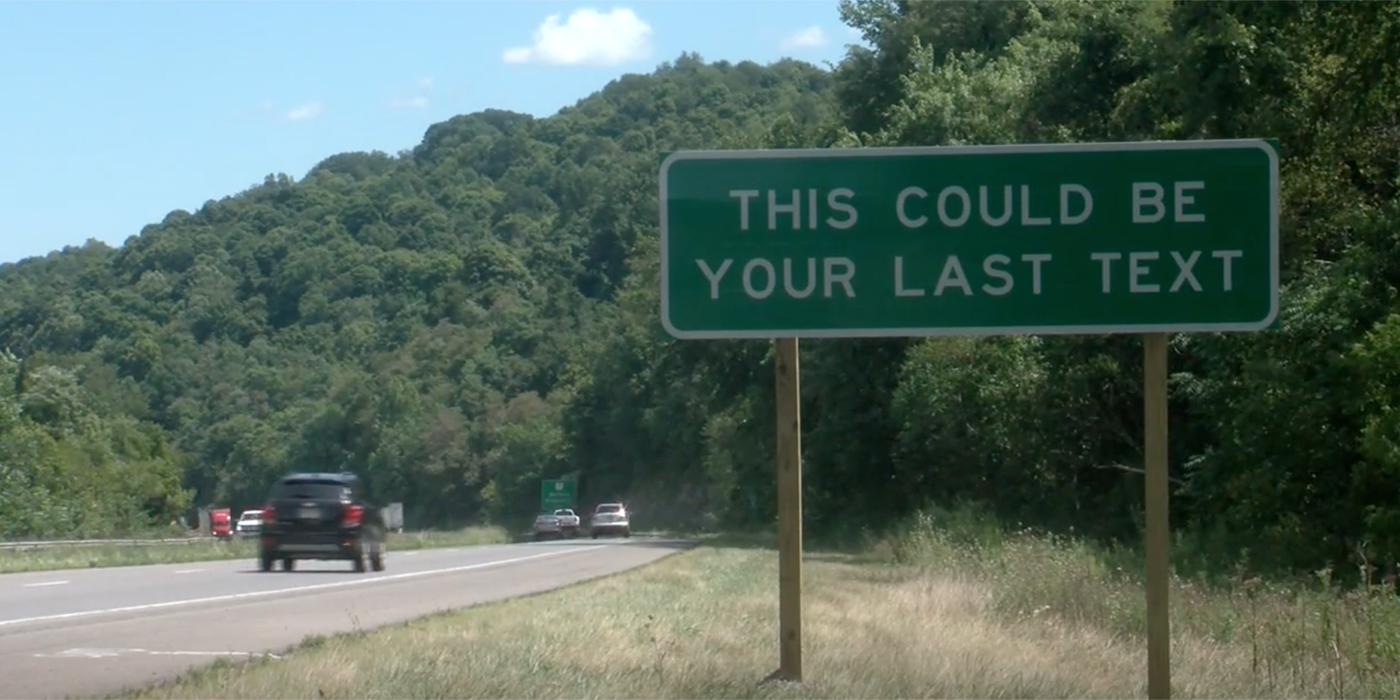

It’s all about repairing cars cheap, fast and better. Insurers and vehicle owners demand a quality car repair at the right price, with no fraud, and done as fast as humanly possible. Consolidators want to be the ones to give it to them.

Consolidators Aren’t Fool Proof

Consolidators, however, may have an Achilles heal. For the short term, consolidators have to entice referral sources with other-than-car-repair offerings: call centers, information-technology sharing stuff, technology-based customer-update systems, rental cars and more. Why? Because they’ve positioned themselves a notch above the independent operators who have equivalent or better basic operations. They’re trying to give both insurers and vehicle owners a single contact point for shop loading, customer care and repair status updates. Consolidators also are trying to form a network, which requires some degree of connectivity between stores and corporate. But these are expensive offerings that can compromise resources in place of improving operational performance (fixing cars efficiently and effectively).

But I’m going to let you in on a little secret: Repairers and even consolidators will never be able to develop and provide customers and insurers with state-of-the-art connectivity loading and customer care services at a level needed to satisfy the future demands of vehicle owners. There are far too many other specialty providers and even insurers themselves who’ll be able to do these things cheaper, faster and better.

Major consolidators can’t afford to divert large dollars and resources away from new acquisition integration and shop-performance improvement strategies to develop high-level call centers, IT solutions and network management capabilities – but they will anyway. That’s the Achilles heal. They’ll try to expand their capabilities in these areas or maybe even partner with a claim-management/IT provider. If and when they do, senior management will begin to lose focus on improving their core processes: autobody repairs.

What’s their thought process in doing this? Some of them think it’ll give them a competitive advantage over the top independents that perform just as well. For now, it’s a good idea for consolidators to improve their front-end and customer management, but I think there will be other providers who emerge and develop a dedicated business model to handle these things. Short term, consolidators are responding to competitive threats, to the need to differentiate themselves and to insurer pressures for them to improve their connectivity to insurance company people and their customers.

Regardless, the fact remains that vehicle owners demand their car to be repaired cheaper, faster and better. All the other information-transfer stuff will be better left to those who can do it cheaper, faster and better. If you’re in the car-repair business – independents and consolidators alike – you had first and foremost better be able to repair cars. Administration and customer care for claim-repair customer demands will ultimately be handled by service providers who are better equipped to fill the intermediary service point between insurers and repairers (large insurers may own and outsource this in-between function).

My prediction for the future: Body shops will have to become autobody repair factories for referral sources rather than being multi-talented in technology, customer care, claims and administrative function. They’ll have to stop trying to own the vehicle owner and, instead, make the referral source their customer. They’ll have to find someone else to do administration and customer care services and learn how to produce a lot of repaired cars from a single location – double or triple single-shift repairs, then multiple shifts and, finally, 24-hours-seven-days-a-week capabilities.

|

Who’s a Consolidator?

|

The Changing Consolidator Landscape

We’ve recently seen strategic investment changes in three of the top consolidators: Allstate’s purchase of Sterling, Ford’s likely sale of Collision Team of America (CTA), and the $30 million investment in Caliber Collision by The Interinsurance Exchange of the Automobile Club of Southern California. For Caliber, this is the second major investment by an insurance-related firm. In 1997, Caliber received funding from Zurich Centre Investments – a subsidiary of Zurich Financial Services Group, which also owns Farmers Insurance Group, the third largest U.S. Property Casualty Insurer.

These investments show that venture capitalists (investors outside the industry) have come to realize that our industry is profitable and that insurers, who are closest to our industry in terms of historical relationships, are gaining a better understanding of how a shop operates and makes money. This implies that shops won’t be able to scream pain as much anymore when negotiating with insurers or claim staff because more and more insurers are gaining an intimate appreciation for a shop’s balance sheet and profit and loss statements.

As for Ford, it this gives us some indication that the OEs may not be as interested in autobody repair as many had thought. (I was one of those people. I thought car manufacturers would cause the next great strategic change in the industry.) But it appears that insurers are more willing to get into the autobody industry than car manufacturers.

So which consolidators in particular will be coming on strong? As I mentioned earlier, Caliber and ABRA are the strongest U.S. players based on size – number of company-owned stores where each shop’s sales revenue is part of company revenue. Fix Auto and CARSTAR both have more stores and the stores have more sales volume, but because they’re franchises, the car-repair sales volume isn’t considered corporate sales revenue.

Caliber is, by far, opening more stores and has the highest overall yearly revenue, but ABRA is also back on track opening stores. This year, it seems, is going to be ABRA’s “catch up to Caliber” year, with 21 new stores planned. Caliber and ABRA also attract capital investors and have proven that they can grow both sales revenue and profits. This attracts outside money and also new entrants into the industry.

There’s also the Boyd Group, a publicly traded Canadian company with 28 U.S. shops and 45 Canadian shops. Boyd is probably second only to Caliber in terms of store and revenue growth. Their profits and revenues have continued to grow, and they’ve continued to open new U.S. stores over the past couple of years, just as Caliber has – while the rest of the consolidators with company-owned stores had slowed new-store openings to almost nothing, opening no more than one or two new stores a year, with some actually decreasing their number of stores.

Clearly most agree that Caliber and ABRA are on top, with Boyd and Sterling coming next. Sterling has yet to show significant store openings recently, but that’ll probably change by year-end. The rest of the consolidators (CARSTAR and Fix Auto aside) are just trying to survive and – in my opinion – are maybe even hoping they’ll be bought out by some of the others. They’re struggling to standardize and integrate their current network of shops, and they don’t have the best access to new capital.

Though I’ve mentioned CARSTAR and Fix Auto because it’s the politically correct thing to do, I consider them big buying groups, and each shop pretty much operates independently of each other. They’re not, in the strictest sense, consolidators. Yet franchises like CARSTAR or this group/member-shop thing offered by Fix Auto are viable options for body shops that want to stay independent while having the ability to negotiate with suppliers and insurers as if they were a large corporation.

Successful Integration: What It Takes

According to Lawrence, Caliber throws a lot of resources at integrating a new shop’s systems and processes. And because at this point Caliber is well-positioned and well-funded, new store growth is solely dependent on effective implementation of the “Caliber Way.” They’ll only acquire a new store that they’re able to integrate quickly and efficiently.

Lawrence says that three shop factors impact how easily a newly acquired shop will change to meet Caliber’s needs:

- Existing IT capabilities – experience using management systems and technology;

- Owner-friendly shop environment – good morale and motivation, the shop has learned to trust and work with management; and

- Receptive culture – shop personnel and management are responsive to teamwork, innovation, sales growth and personal development.

|

Consolidation: The Time Is Right

|

Money, insurance relationships and people are key growth factors, but for Caliber – which has worked hard to solve these issues – it’s only the ability to successfully roll a shop into the Caliber fold that constrains growth.

Caliber places a premium on assuring that the first store in a new market does a good job and is successful with the primary customers, insurers and employees. If the first store struggles, it’ll be difficult to gain the trust needed to draw the best employees and attain additional direct-repair agreements for other candidates in the market.

It seems that Caliber is more likely than other consolidators to forgo the opportunity to purchase a prospective shop if they feel it won’t successfully and effectively integrate into the overall Caliber culture, operating style, etc. They’ve found through trial and error (as has ABRA) that not every prospective acquisition will be able to meet, easily adapt to or learn to adapt to their standards.

Why? There could be, for example, problems with management or staff (poor leaders, management and employees are in conflict, no sense of company goals or team work, “us against them” shop atmosphere); the shop may not have the type of DRP relationships in which insurers will transfer over to new ownership; the building isn’t acceptable due to age, layout, equipment or location within the market area; or the local economy is depressed or not growing.

Consolidators have learned that several factors influence how effectively a shop will integrate into a corporate structure. They’re no longer looking at just a few factors. They used to, however, just look at store size, condition of the hard building and equipment, and sales volume – and paid minor attention to management, staff and existing DRP relationships. They thought they’d be able to develop these other areas relatively easily, but that wasn’t the case. That’s why over the past two years, network growth has slowed to a crawl – they’ve all been trying to integrate the numerous shops they purchased in the late 1990s.

And it appears that only Caliber, ABRA and Boyd have ironed out these integration challenges because they’re continuing to grow in both overall sales and number of stores. Caliber, though, seems to be pulling away. By the end of 2002, they expect annual sales to be approximately $300 million. But Sterling may also come on strong this year, like ABRA, with 20 or so new stores.

Based on what consolidators have learned, they’ve realized that entering a new market through acquisition is more complex than they initially thought. These days, Caliber looks at:

- Market demographics (population spending power and size);

- Physical nature of candidate shop or facility;

- Existing and potential DRP relationships; and

- Management and staff – local leaders who can draw more good people.

For example, Lawrence noted that the Northern California marketplace has great potential for Caliber – the demographics and insurers are there, but it’s difficult for Caliber to find the right shop platform that also has the people (see points 2 and 4 above).

Divvying Up DRP Dollars

In terms of insurance company relationships, both Adlemann and Lawrence understand that relationship-building starts with front-line claims personnel and moves up higher in the organization. Having a strong relationship with insurance company executives is important, but they both agree that local claims personnel have to be sold first on the value each consolidator brings to the market. It’s a much easier pitch to senior insurance company management if their own people have a favorable opinion.

Both also agree that their shops have to deliver and compete with local independents for insurance referral work. Each shop has to prove itself on the local level. The difference is that the consolidator just keeps selling and selling and does everything it can to make the relationship positive. And the selling feature to local insurers is that they’re able to go to a single source to resolve problems versus having to fight shop by shop.

Consolidators are more aggressive than most independents. And they’ll keep pushing to improve market share and their competitive advantage (operations, relationships and employees). Think about it. How motivated is an independent shop owner to keep pushing if he’s already pulling down anywhere from $200k to $500k a year? Most independents just aren’t that aggressive once they’ve reached a certain level of success. But they’re going to have to learn to push and to continue improving – not just to make more money, but just to remain competitive.

Still, there are plenty of DRP dollars to go around to independent body shops, and more is expected to come if insurers are able to improve their referral capabilities. Recent estimates show that large consolidators, including franchise models, may be doing about $1 billion yearly in sales, so they have a long way to grow to keep up with insurer demand for DRP-type providers. Based on 2000 research and data, claim dollars spent by insurers to repair cars is closer to $30 billion a year.

Although insurers are catering more toward consolidators and multi-store repair providers, they’re also keenly aware that qualified non-consolidator body shops are needed for the foreseeable future to meet vehicle owner demand for DRP services. If, however, the supply of independents able to meet policyholder demand diminishes, insurers will encourage, finance or become consolidators themselves in order to put a greater numbers of shops and more DRP capacity into the marketplace.

Writer Jake Snyder is the principle of CR Management Systems, a consulting, training and business-development company. He’s been in the industry for more than 15 years, has managed a collision repair facility, held various claims positions with Allstate Insurance Company, and performed consulting and product development for Body Shop Video’s, Business Development Group. Snyder can be contacted at (732) 886-5340 or at [email protected].