Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the March 2005 edition of BodyShop Business.

“Let the games begin.”

I can’t be certain, but experience tells me that phrase was on the minds of a number of automobile insurance company executives on March 27, 1964.

Why on that date, you ask? Because that was the day after the Supreme Court of Alabama ruled that State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Company could be held directly liable for the death of a young man who was killed in a car accident if, and only if, it could be proven that State Farm had selected the body shop where the vehicle had been negligently repaired a few months before the fatal accident.

The Alabama case set the stage for what most body shop owners would consider to be the biggest problem facing the collision repair industry today: steering.

By the term “steering,” I mean tactics or games insurance companies use to pressure a policyholder to have his vehicle repaired at a particular body shop, while at the same time, trying to avoid any liability associated with the repairs performed by the insurer’s preferred shop.

To understand the game, you first have to understand that practically every policy of property-damage insurance (e.g., automobile, homeowners, commercial-property) sold in the United States for the past 150 years or so contains what’s commonly referred to as a “Payment of Loss” provision (POL provision).

POL provisions essentially give an insurance company two options for paying a claim to repair property that’s been damaged but not destroyed. The first option is to pay the policyholder’s claim in money so the consumer can have the repairs performed by an independent contractor of his choice.

The second option is for the insurer to hire the contractor itself and to exercise direct control over the scope, method and cost of repairs. It’s this second option that gave rise to direct-repair programs (DRPs).

But the fact that insurance companies generally do contain a POL provision leads to a rather obvious question: If insurers have the right to hire a body shop to fix one of their policyholder’s cars and to directly manage the cost of such repairs, why don’t they just go ahead and do it on every claim?

The answer is liability.

The Alabama case and others like it make it clear that if an insurance company exercises its option to repair a damaged car by selecting the body shop that will do the work, the insurer can be held directly liable for the quality and safety of the repairs performed. In other words, while an insurer may very well have the right to tell a consumer to take his car to a particular body shop for repairs, the insurer would then have to assume the liability for the quality and safety of the repairs performed by that shop.

And apparently that’s a risk most insurers are unwilling to take.

So what insurers decided to do instead was to try and “play both sides of the fence” by developing word tracks and other schemes to pressure policyholders to use their DRP shops or other shops that their agents or adjusters have a “friendly” relationship with – without creating a paper trail to prove that the insurer selected the body shop that performed the repairs. That way, if a problem developed with regard to the repairs or if someone was injured or killed as a result of the shop’s negligent work, the insurer could claim that it was ultimately the consumer who chose the shop that performed the shoddy work.

There can be no question that these tactics are working. According to the 2004 BodyShop Business Industry Profile, for example, more than 76 percent of the owners of “non-DRP shops” surveyed said steering was adversely affecting their businesses. Even more surprising and disturbing is the fact that a full 80 percent of the owners of “DRP shops” said steering was having a negative impact on their businesses.

These statistics should send a chill down the spine of every body shop owner who has a long-term interest in the success of his business, as well as every consumer who finds themselves in a situation where they’re feeling pressured to have their vehicles repaired at a body shop recommended by an insurance company.

Why? Because these stats present compelling evidence that at least some insurance companies are systematically steering consumers away from body shops that perform quality work at a competitive price. You see, if one accepts the premise that insurance companies truly care about the quality of repairs performed to their policyholders’ vehicles and therefore select only those shops that perform quality repairs at the most competitive price to participate in their DRPs, it makes absolutely no sense that 80 percent of DRP shops are having work steered away from their shops by other insurance companies.

Unfortunately, the most logical explanation for this situation is that some body shops have obtained either the explicit or implicit approval of insurance companies to cut corners and to otherwise compromise the quality of the repairs they perform in order to undercut the competition on price. And, common sense dictates that this is being done to secure more referral work from those insurance companies that either actively encourage the practice or, at the least, turn a blind eye to it in order to save money on claims.

There is, of course, quite a bit of irony to the fact that DRP shops are now complaining about steering in even greater numbers than non-DRP shops. Nevertheless, it does send a loud and clear message that no body shop – regardless of its size, ability to perform quality repairs at a competitive price, and status as a DRP shop or non-DRP shop – is immune from steering.

That’s the bad news. The good news, however, is that there is something that every shop and consumer can do to protect themselves, as much as possible, from getting caught up in the game.

For this strategy to be truly effective, though, you must understand how and why the rules regarding POL provisions developed. Accordingly, the intent of this article is to give you a limited history of the law regarding POL provisions so that you can use that knowledge to compete more successfully in the future.

However, because policies are different and insurance laws vary from state to state, this article shouldn’t be construed as legal advice or as a statement of the law. Therefore, you should always seek the advice of a competent attorney who is knowledgeable about the laws in your particular state.

The Strategy

Protect yourself, your shop and your prospective customers against insurers’ games and tactics by implementing this straightforward strategy:

The consumer should request that the insurer commit, in writing, as to which payment option it’s exercising. And, if the insurer decides to exercise its option to repair, the consumer should insist that the insurer specify the name of the one body shop where the insurer wants the car repaired. That way, all of the parties involved in the transaction – the consumer, the shop and the insurer – will have a better understanding of what their respective rights and obligations are. It should also go a long way toward eliminating some of the nonsense that characterizes the way claims are currently being adjusted and handled.

Will it work? It has in the past and should continue to do so in the future. The main reason is that the approach is based on solid rules of law developed by our courts to protect consumers from efforts by insurance companies to interpret POL provisions in an unfair manner. Indeed, the decisions handed down by the courts in a number of jurisdictions are so clear and make such good common sense that it’s surprising that the situation got so bad in the first place.

But, as I mentioned earlier, you need an understanding of POL provisions to effectively use this strategy.

Insurers Have 3 Options

POL provisions are usually found in either the “Property Damage” or “Conditions” section of a policy of physical-damage insurance and typically read as follows:

Payment of Loss

“Physical Damage” Coverages

The Company may, at its option, pay for the loss in money; OR may repair OR replace the damaged or stolen property.

As stated above, these provisions essentially give an insurance company three options for settling a claim for damage to an automobile. The insurer can:

1) Pay the loss in money so that the policyholder can have the vehicle repaired by an independent contractor;

2) Repair the vehicle itself (i.e., exercise the “direct repair” option); or,

3) Deem the vehicle a total loss.

Courts have generally been quick to enforce POL provisions because, when properly interpreted and applied, they strike a fair balance between the interests an insurer has in controlling claim costs while also protecting the insured’s interests in making sure that his property is repaired safely and properly.

Not surprisingly, though, because courts have had experience dealing with insurers that have tried to interpret POL provisions unfairly and those that have tried to escape liability if the repairs they’ve directed aren’t performed properly, three rules have developed regarding POL provisions.

3 Rules Regarding POL Provisions

1) The insurer must clearly and unambiguously notify the insured at the outset of the claim as to which payment option it’s exercising. Howard v. Reserve Insurance Company, 117 Ill. App. 2d 390, 254 N.E.2d 631 (1st Dist. 1969). And if the insurer fails to do so, it will be deemed to have waived its direct-repair option. Id.

2) The two repair options are mutually exclusive and, therefore, an insurer generally cannot purport to pay a claim in money based on the amount that it believes it could have had the property repaired for if it had exercised its direct-repair option at the outset of the claim. Keystone Paper Mills v. Pennsylvania Fire Ins. Co. et al., 291 Pa. 119, 139 A. 627 (Pa. 1927).

3) If the insurer does exercise its option to repair the property, it must accept direct responsibility for the quality and safety of repairs performed by the contractors it hired. Mockmore v. Stone, 143 Ill. App. 3d 916, 493 N.E.2d 746 (3rd Dist. 1986).

Insurers Must Be Clear

Perhaps the best way to explain how these rules could help you prevent prospective customers from being steered away from your business is to start with the case of Howard v. Reserve Insurance Company. The Howard case involved a fire loss to a building located in Chicago. Following the fire, the insurance company sent the policyholder a letter that quoted the policy language setting forth the insurer’s option to repair, rebuild or replace the damaged property.

Thereafter, the parties discussed the value of the claim in terms of the cost of necessary repairs. However, when the insurer later learned that the insured was in the process of repairing the building, the insurer attempted to deny all liability for the loss based on a contention that the insured had breached the POL provision in the policy by depriving the insurer of its option to repair or rebuild the property itself.

The insured subsequently sued the insurer for breach of contract and won at both the trial court and on appeal. In reaching its decision, the Illinois Appellate Court emphasized the importance of clear communication of an insurer’s election of its repair option to its policyholder. For instance, the court stated:

“In insurance contracts, as in all other contracts, it is incumbent upon the parties to deal with each other in a plain, simple and straightforward manner, and, where an election is to be exercised under a contract, notice should be made in such a manner as to leave no doubt in the mind of the opposite party of an intention to exercise it.”

What body shop owners might also find interesting is that the court quoted the following statement that the trial judge made in rejecting the insurance company’s argument that it had adequately notified the insured of its option to repair the property rather than pay the loss in money:

“This letter [date] that was sent did not exercise the option [to repair], and following that letter, negotiations were going on with the adjusters for the companies with regard to amounts, and if the company had taken the position that they would exercise that option, even if that letter didn’t so indicate it, it was the duty of these adjusters to say, ‘Why do we talk about money? We don’t care what you’re asking or what the price is. We’re going to do that ourselves.’ “

The court in Howard then went on to adopt five criteria to make the notice of election to repair or rebuild by an insurance company effective:

1) It must be made within a reasonable time after the damage or loss has occurred to the insured;

2) It must be clear, positive, distinct and unambiguous;

3) The repairs or replacements must be made within a reasonable time;

4) It cannot be coupled with an offer of compromise or be made for the purpose of forcing a compromise, but it must be an election made with no alternative; and,

5) When the election is made, the repair or replacement must be suitable and adequate.

It is, to say the least, interesting to consider some of the classic statements by insurance companies, such as the one that, “You can get your vehicle repaired anywhere you want, but the most we’re going to pay is the amount of our estimate,” in light of the criteria set forth in Howard.

Options Are Mutually Exclusive

Another case that didn’t involve car repairs but that body shop owners may find interesting is Keystone Paper Mills v. Pennsylvania Fire Ins. Co. et al., 291 Pa. 119, 139 A. 627 (Pa. 1927).

In that case, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court examined the meaning and effect of a typical POL provision and found that, not only is the preparation of an estimate of repair costs inconsistent with an insurer’s election of the option to repair, but also that an insurer cannot limit its payment of a claim based on a contention that some repairman might be able to perform the necessary repairs for the amount specified in the insurance company’s estimate of repair costs.

In Keystone, a corporation that operated a paper mill filed suit against five of its insurers after a fire severely damaged one of its paper presses and the insurers vacillated about how they were going to pay for the loss. The policies contained POL provisions that gave the insurers the right to repair or rebuild the machinery themselves but, rather than exercising that option, the insurers arranged for two engineers to submit estimates of the cost of probable repairs. The insurers then tried to limit their payment on the claim to the engineers’ estimate amounts.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court agreed with the trial court that such conduct constituted a breach of the insurance contract. As a preliminary matter, the court observed that, if an insurance company is going to elect to repair or rebuild a piece of machinery, there would be no need for an estimate of repair costs.

The court then went on to state that an insurer’s preparation of an estimate of repairs, coupled with an offer to either pay the estimated amount or repair the machinery, would not amount to an exercise of the insurer’s option to repair. The court reasoned, as follows:

“Had the Keystone Paper Company accepted any of the offers by these [engineers], depending on the insurer to make good in keeping with the terms of the agreement, it would have faced a controversy of a nature not covered by the policy. The insurance company’s burden would have been shifted to that of the repair company.

“There is nothing in the contract of insurance that required the insured to accept the responsibility of the repair company, as the court below has well observed. Had the insurance company wished to take advantage of its option to repair, it could have made a contract with [the engineers] and subjected itself to the full responsibility of the policy –- to furnish a machine as good and as serviceable as the one that was in use.

“The [insurers] cannot seize upon offers made by others, appropriate them to their use as an exercise of their right, and then hold the [policyholder] to the submitted estimate. … Had [the insurers] elected to repair and it had been accepted, there would have been no estimate. Had the companies estimated the cost of repair and submitted the alternative proposition, either to pay the estimate or repair, this would not amount to an acceptance of the option within the policy. Persons unaccustomed to negotiations of this character are not to be put to the hazard of such propositions by experienced dealers in such transactions.”

Note: I added the italics for emphasis.

Thus, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court recognized that the insurers were playing the same type of legally sophisticated game with their insured back in 1927 that automobile insurers play with their policyholders today. The object of the game is for an insurer to strictly control the cost of repairs while at the same time trying to distance itself from any liability associated with inadequate or negligent repairs.

The telltale sign of the game in the Pennsylvania case was that, if the insurers truly believed that the repair bids submitted by the engineers would have allowed for the paper press to be restored to its pre-loss condition, they had every right to contract with the engineers directly and assume the liability that those repairs would be successful.

On the other hand, however, the insurers had no right to present the engineers’ repair bids to the insured and try to force the insured to contract with the engineers since, by doing so, it would have made it appear that the insurers had opted to pay the claim in money and that the policyholder actually hired the engineers to perform the work.

Fortunately, the court recognized that what the insurers were really trying to do was shield themselves from liability in the event the work their engineers were proposing to do didn’t restore the machinery to its pre-loss condition. As a result, the court concluded that an insurer’s offer of a third person to perform repairs to insured property will not be considered an exercise of the option to repair by the insurer unless the insurer directs the repairs and assumes responsibility for the contractor’s work.

With regard to modern-day collision repairs, it’s clear that insurance companies that engage in the type of steering discussed above are trying to put their policyholders into an even more precarious position than the insurers in Keystone tried to put their policyholder in.

To begin with, cars today are more complex than ever, and consumers generally would have no way of determining the extent of collision damage or the scope of necessary repairs. Therefore, consumers shouldn’t be put to the hazard of having to choose between:

1) Getting a vehicle repaired at a body shop recommended by the insurance company without a written assurance that the insurer will accept direct liability for the quality and safety of the repairs performed by its preferred shop; or,

2) Having the repairs performed at a body shop the policyholder trusts but having to pay more than the deductible amount specified in the policy because of an insurance company’s claim that one of its DRP shops could have performed the repairs for less money.

Either situation is completely untenable considering that, if an insurer truly believes that it can get an automobile safely and properly repaired for less than the policyholder can get the work done for, all it would have to do is exercise its option to repair and assure the policyholder that it will assume direct liability for the success of the repairs.

Insurer Liable

The rules regarding POL provisions take on even greater meaning in the context of claims to recover the necessary costs of repairs under an automobile policy. The main reasons are that, not only is there a greater likelihood of gamesmanship and outright abuse given the disparity in the knowledge and bargaining power of the parties to this type of contract, but also because there are genuine safety and liability issues associated with cheap automobile repairs. Two cases illustrate these points.

The first case is Mockmore v. Stone, 143 Ill. App. 3d 916, 493 N.E.2d 746 (3rd Dist. 1986). In Mockmore, the policyholder insured his recreational vehicle under a policy of physical damage insurance issued by State Farm. The vehicle was subsequently damaged in a collision, and State Farm told the plaintiff to take it to a particular repair shop for repairs.

After the repairs were completed, however, the insured discovered that the poor quality of the repairs allowed water to seep into the vehicle causing further damage. Although the policyholder brought the matter to State Farm’s attention, State Farm refused to pay the costs incurred by the policyholder to have the additional damage repaired.

The policyholder subsequently filed a lawsuit against both the repair shop and State Farm alleging, among other things, that State Farm’s refusal to pay for the necessary re-repairs constituted a breach of the insurance contract.

Ultimately, the trial court dismissed the policyholder’s fourth amended complaint against State Farm after agreeing with the insurer that it couldn’t be held liable for the policyholder’s damages because the body shop that performed the work was an independent contractor.

On appeal, the Illinois Appellate Court noted that the issue of whether an insurance company could be held responsible for the quality of repairs performed by an independent contractor had not previously been decided in Illinois. It therefore looked to numerous cases from other jurisdictions where the courts had recognized a policyholder’s right to bring an action against an insurance company for negligent repairs notwithstanding the fact that an independent contractor had performed the repairs.

In reaching its decision to reverse the trial court and to reinstate the policyholder’s case against State Farm, the court focused on the meaning and effect of language in State Farm’s policy that was similar to POL provisions found in other policies. It determined that the provision gave State Farm the option to repair the vehicle at a shop of its choice in lieu of paying the claim in money. However, it also determined that the option to repair carried with it a contractual liability for damages resulting from negligent repairs.

In support of this conclusion, the court quoted a well-respected treatise on insurance law:

“Where the insurer exercises its option to repair, it is in the same legal position as any person making repairs, insofar as liability to strangers is concerned. Consequently, where a collision insurer has agreed to repair and actively takes the matter in hand, making all necessary arrangements, the reasonable conclusion is that the insurer thereby assumes the duty of having the repairs made with due care; and it is not relieved of this duty merely because it chooses to select an independent contractor to make the repairs, and refrains from exercising any supervision over his work.”

The court then analyzed cases from other jurisdictions illustrating the application of that rule to circumstances wherein the insurer was held liable for the results of the negligent repair of a motor vehicle and concluded that, “The major thrust of the rule is that the insurer’s election to repair the vehicle together with its selection of the means by which such repairs are to be accomplished imposes a contractual liability for damages resulting from negligent repairs.”

Consequently, it held that, because State Farm not only elected to repair the vehicle but also directed that the repairs be undertaken by a particular repair shop, State Farm’s contractual responsibility included the damages resulting from allegedly negligent repair.

The second, and even more compelling case with regard to an insurance company’s liability for negligent repairs, is the Alabama case mentioned at the beginning of this article: State Farm v. Dodd, 276 Ala. 410, 162 So.2d 621 (1964).

In that case, a State Farm insured was involved in a collision that caused damage to the front end of his vehicle. Following the loss, the vehicle was taken to a repair shop chosen by the insured, but it was later moved to two other repair shops, allegedly at the insistence of State Farm representatives. The vehicle was eventually repaired at the third shop and, shortly after the policyholder picked it up, he noticed that it would occasionally dart to the left when driven.

The policyholder complained to the shop that performed the repairs on a number of occasions, and each time, he followed the shop’s recommendation for fixing the problem. However, the problem persisted, and one day when the policyholder’s son was driving the vehicle, it darted to the left and struck a bridge abutment, killing the boy.

The son’s estate filed a lawsuit, alleging that both State Farm and the third repair shop were liable for the son’s death. As in the Mockmore case discussed above, State Farm defended the action, saying the repair shop that performed the repairs was an independent contractor and, therefore, the insurer could not be held liable for the boy’s death.

At trial, a verdict was returned against both State Farm and the repair shop, and the insurer appealed the decision. When the case reached the Alabama Supreme Court, the court agreed that if it could be proven that State Farm had selected the repair facility that performed the negligent work, the insurer could be held liable for the boy’s death.

However, the court also determined that the evidence wasn’t clear enough on the issue of whether State Farm actually selected the repair facility that performed the negligent work, so it sent the case back to the trial court for that issue to be further investigated and decided.

Thus, Mockmore and Dodd provide valuable insight as to why certain insurers engage in steering. Simply put, it forces unsophisticated policyholders into the Catch-22 position of having to pay sums above the deductible amounts stated in their policies to have a shop of their choice perform the necessary repairs, or it forces the insured to go to one of the shops on the insurer’s list without there being any clear evidence, i.e., a paper trail, establishing that the insurer effectively chose the body shop that performed the repairs.

Failure to Notify

One question that logically follows from what has been said above is: What happens if an insurance company fails or refuses to notify its insured as to which payment option it’s choosing?

In Illinois, for example, that question was put to rest long ago when our Supreme Court stated in a case called The Insurance Company of North America v. Hope, 58 Ill. 75 (1871) that, “The right of the company to replace or repair the property insured, in case of loss, is created by the provisions of the policy, and if the company does not make its election in apt time, and give the assured notice, the right to so build or repair does not exist.”

In addition to the Supreme Court of Illinois, the authorities that have considered the scope of the repair-rebuild-replace clause are unanimous in their findings that a failure by an insurer to notify its insured of its election to exercise the option to repair by some unequivocal, clear, positive, distinct and unambiguous act will be deemed a waiver of the insurer’s right to raise the option as grounds to reduce the policyholder’s claim or as a defense to an action on the policy. (See, e.g., 12 Couch on Insurance §176:17-18 (3rd ed.); 6 Appleman Insurance Law and Practice Ch. §171:4003).

The rationale is that, because an option to repair or rebuild is inserted for the benefit of the insurer alone, the insurer is permitted to waive its right to rebuild under the option clause so as to prevent insistence thereon. 12 Couch on Insurance §176:7 (3rd ed.).

Implementing the Strategy

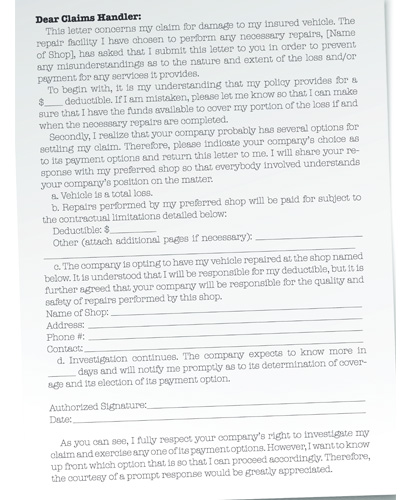

A simple and straightforward letter such as the following should prove effective in curbing the types of games and tactics insurers use to steer customers to a particular body shop while trying to avoid any liability associated with the repairs:

Sidebar 1: How Insurers Steer Work

Different insurance companies use different steering tactics. In my experience, however, the most common tactics seem to be:

1) Telling a policyholder that the processing of his claim will be significantly delayed unless he has the vehicle repaired at one of the insurer’s preferred shops;

2) Writing estimates based on below-market labor rates and then telling the policyholder that, because the insurer has a list of shops in the area that will honor those rates, he’ll be responsible for paying more than the deductible amount stated in the policy unless he has his vehicle repaired at one of the shops on the insurer’s list;

3) Threatening to not approve or to arbitrarily limit an insured’s rental coverage unless he has his vehicle repaired at the insurer’s preferred shop; and,

4) Disparaging non-DRP shops by telling consumers that these shops commit fraud or that their work is shoddy.

Sidebar 2: Consumers in a Catch-22

Insurer steering tactics force unsophisticated policyholders into a Catch-22 position of either:

- Having to pay sums above the deductible amounts stated in their policies to have a shop of their choice perform the necessary repairs, or

- Being forced to go to one of the shops on the insurance company’s list without there being any clear evidence, i.e., a paper trail, establishing that the insurer effectively chose the body shop that performed the repairs.