How small is small? Is a three-man shop small? A two-man shop? Depends on whom you ask. But, by any definition, a one-man shop is small. And one of the most successful one-man shops I’ve ever seen is in a small town in Iowa. How many one-man shops do you know with a heated downdraft spraybooth and a prep station? Dave Stephenson — owner, chief cook and bottle washer of Stephenson Body and Fender in tiny Vinton, Iowa — has all of that … and more. He’s turned a one-man shop into a well-oiled, money-making machine. How? By making the absolute most of out what he’s got.

So, before you start planning to build a new, state-of-the-art facility or hire more technicians because your current shop just isn’t bringing in enough profits, consider how Stephenson’s strategies could work for you.

Small Beginnings

Extremely successful shop owners who’ve grown their businesses to large volume and have many employees sometimes long to get back to where they started. Wouldn’t it be more fun to have no one to worry about except yourself, they often muse.

Extremely successful shop owners who’ve grown their businesses to large volume and have many employees sometimes long to get back to where they started. Wouldn’t it be more fun to have no one to worry about except yourself, they often muse.

How does a guy like Stephenson build a body shop profitable enough to own the big boy’s toys all by himself? Parts of his story sound very familiar. When he graduated from high school in 1979, he intended to enroll in the local vo-tech autobody program. Before he could start classes, the long-time autobody technician at the local Ford garage offered to teach Stephenson the trade if he’d work for just "gas money." For six or eight months, he reported for work in the metal Quonset hut that served as the Ford dealer’s body shop. Like every beginning technician, Stephenson learned how to sand, mask and disassemble cars while his tutor did the money work.

I asked Stephenson what his mentor taught him that was still part of his routine today. I was thinking skills like running lead or shrinking with a torch would be hard to acquire these days. Stephenson answered immediately that the most important thing he learned from the man who taught him his trade was that there’s only one way to do the repair: like it was your own car. If you prepped and sanded and pulled and painted like it was yours, your customer would be pleased and return the next time. Stephenson’s current success is rooted in that philosophy. Of course, to get where he is today, you don’t just have to be good; you’ve got to be fast too.

By the time Stephenson was 21, the Ford dealership had changed hands, and he was running the body shop. By this time, he knew a little something about the actual repair but still needed to learn to sell the work to the customer and to keep the shop running in the black to suit the dealer. The school of hard-knocks applies to learning the paperwork as well as the metal work.

Building a Reputation

In 1983, the Ford store changed hands again, so Stephenson rented a 3,200-square-foot building in Vinton, Iowa (population 5,600) and hung up the Stephenson Body & Fender shingle. He put what he’d learned about dealing with the public to good use and started building a nice repeat business. At this point, his rented shop had a homemade crossdraft booth and little else in the way of equipment.

After five years of paying rent, he bought a 40-foot by 80-foot former feed store on the edge of town. Taking nine months off from doing body work (he must have made some money in that rented building), Stephenson remodeled the new building himself. He poured concrete, built walls, strung wire, sweated pipes and made cabinets. When you’re good with your hands, it carries over. I built a dog house once. The dog refused to go in it.

After Stephenson went back to doing body work in his own building, his sales volume grew to a six-week backlog, which he still has today. One of the biggest problems with a one-man shop is you can only do so much. By 1992, his homemade crossdraft booth with enclosed lights and an explosion-proof fan wasn’t productive enough, so I sold him a downdraft prep station that he installed inside his existing booth enclosure. Again, Stephenson saved considerably by digging and pouring his own trench — not to mention assembling the unit, plumbing the airlines and running the exhaust stacking. As in any small town, he was owed a favor or two from the backhoe guy and the electrician who traded their labor for some of Stephenson’s fine work.

Now that Stephenson could paint the work faster, his business continued to grow and he needed more space. So, in 1993, he added another 40-foot by 80-foot building onto the back of the first. As you might guess, he did most of the construction himself. In it, he built a nice paint-mixing room because he always wanted one and recognized early on that mixing your own color was the best way to save money on materials. (And, frankly, he was tired of having it out in the open shop.) He also illuminated the heck out of the new addition by installing recessed fluorescent fixtures in every possible corner.

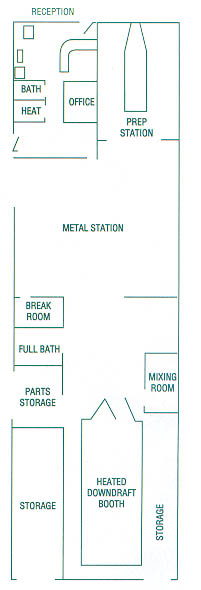

Stephenson’s 40-foot by 80-foot addition houses the mixing room, the downdraft booth, the break room, a full bathroom with a shower, parts storage and space for several cars to dry or be reassembled. As you might imagine, he has many cars in process at one time. As filler dries on one, he pulls the kink out of another or spot welds panels on the next. The heavy sanding is done under the prep station or at least under the large volume air cleaner. Stephenson is in the market for yet another air purifier to capture more of the airborne dust that makes life hell in any body shop.

In 1996, Stephenson still couldn’t produce clean paint work fast enough to suit himself, so he started to look for a used downdraft spraybooth — not an everyday find in rural Iowa, I might add. After some searching, he located a new-car dealer in a town about 150 miles away that had a two-year-old booth the owner didn’t want to move to the new dealership. The owner sold the booth to Stephenson for $15,000. It had to be disassembled and moved, but it included all the exhaust stacking, electrical conduit and switching to make it function. This time, Stephenson hired out the teardown and removal to a hauling company, but reassembled it very cleverly. Once he’d hired someone to excavate and pour the new trench (evidently, he didn’t have so much fun last time), he hired a spraybooth contractor to straw-boss the assembly process. Stephenson, the booth specialist and three local guys had it in, up and running in two days. Today, Stephenson finds the booth not only speeds up the paint work but also makes a super closing tool. Just walking the customer back into the shop to see the last car sparkling clean in the booth makes the sale easy.

Making Every Job Count

Stephenson hasn’t always focused on the most profitable collision work like he does now. He went through two years where he did restorations and street rods. He says it was satisfying to do the perfect job, but it was hard to make any money at it. Time and materials aren’t nearly as profitable as beating the flat rate on collision repair.

Today, he hunts for the most profitable work. It’s no secret that damage between $2,000 and $4,000 on a five-year-old or newer vehicle will make the body shop the most money. If it were only you, wouldn’t you want those specific jobs, too? Stephenson does. So he spends extra time selling those customers on his shop. Stephenson writes the estimate, orders the parts, stages the parts (he uses parts carts to keep the stuff together and handy) pulls the frame, hangs the parts, paints the repair and details the car. Nothing to it right? His success is a direct result of hard work and long hours — and each car is repaired as if it were his own.

Big-Time Tools

Stephenson’s problems are just like those in your shop; he simply tries hard to make the next step as easy as possible for himself. In your shop, the metal man wants to hand off to the painter with 80 grit D/A marks in the work and let the painter smooth it out. Stephenson, of course, does it all and owns as many different power sanders as there are made. Studies show that any painter spends almost one third of the time sanding something. The secret is to have a power sander that’s the right size, shape and stroke for every sanding task. Stephenson has them all and uses them all every day. How can one guy get so much done? Those extra power sanders are part of the answer.

Rapid production is a priority in any shop, but when it’s just you doing the all the work, tools become even more important. You could drive a pretty nice car for less than Stephenson has tied up in his hand-tool roller chest alone.

The first piece of real equipment, besides an air compressor, that Stephenson bought was a wire welder, which was kept under a tarp in the tool area and looked as clean as when he first acquired it. He was an early convert to a pin welder to pull dents out quickly. He’s also a big fan of his pin-less resistance welder. It’s even faster because the slide hammer itself is welded to the panel and after the crease is out, there are no pins to remove. He also has a plasma cutter to cut off the damaged parts quickly.

Stephenson also uses a straightening system that ties a unicoupe car to the floor securely and two posts to pull it around. He does his measurement with a set of centerline gauges but is in the market for a 3-D measurement system. Not because he can’t get the cars straight, but because a 3-D system is faster. Now he has to pull, release and re-measure each time. With a measurement jig, when the pin hits the hole, stop, you’re there. As if that doesn’t sound like a one-man shop full of equipment already, Stephenson also owns a gun washer, a parts washer, a pressure-feed sandblaster, a hydraulic lift, bumper jacks, a desiccant drier and a heavy-duty sewing machine to do some of his own trim work.

Small Shop, Big Success

What’s on Stephenson’s wish list for the future? He wants to switch his prep station from a drive-in to a drive-through so he can use that same stall for inside estimating as well as sanding. He plans to do his own trench and duct work and install the new overhead door to make the change. He’s also in the market for an extra-wide, above-floor hoist that he can locate in the aisleway in front of the booth. He wants one wide enough that he can drive another car under the one in process up on the hoist. He’d also like to cement his parking lot — no doubt in his free time. And he’s considering buying a wrecker to haul the non-driveables in.

Not only has Stephenson built himself one of the best-equipped one-man body shops I’ve ever seen, he’s also bought a second home on a lake in Missouri and looks forward to spending more time boating with his family.

The moral of this story might be that the next time you’re tempted to add another employee to keep up, look instead to buying more productive equipment and to smoothing out the work flow from the sale to the delivery. It’s a business philosophy that’s worked wonders for a one-man shop in a tiny Iowa town.

Writer Mark Clark, former owner of Professional PBE Systems in Waterloo, Iowa, is a well-known industry speaker and consultant. He’s been a contributing editor to BodyShop Business since 1988.

|

No Man is an Island Doesn’t this guy ever get tired of doing it all himself? From time to time, yes. Stephenson did hire an employee years ago when his backlog got too big. After all, people will only wait so long for a repair, even in a small town. His first guy had to learn to do it Stephenson’s way and did it for about three years, until he quit to take another job. Stephenson spent the next few years alone until the backlog bothered him again. This time, he hired a community college autobody graduate and taught the kid to do it his way. After about 18 months, |